Overview of the Visual Arts in North Carolina, 1930s-1950s

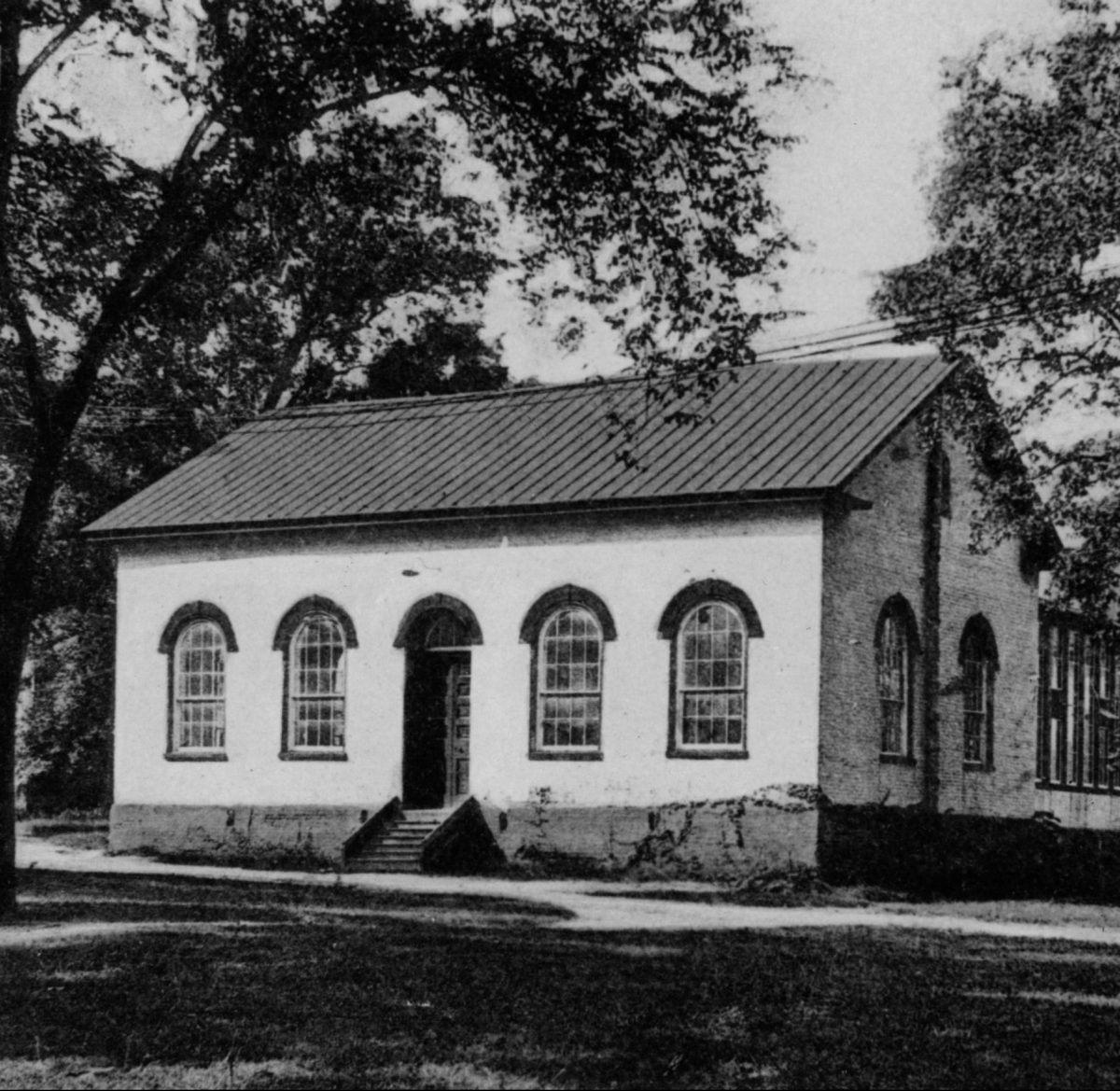

Interest in the arts in North Carolina grew significantly during the mid-1930s. Under the influence of the New Deal Federal Arts Project, a branch of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), nine art centers had been created in the state. Spurred by this assistance from federal programs, as well as by a donation from the state’s most persuasive advocate for the arts, Katherine Pendleton Arrington, the University decided in 1936 to renovate its eighteenth-century chapel, Person Hall, as a place for teaching and exhibiting art.

The University’s commitment had come about almost by chance. North Carolina law required that all elementary school teachers take art courses, and each summer the Department of Education brought visiting artists to the Chapel Hill campus. In 1934 and again in 1935, Francis Speight, probably North Carolina’s most famous artist, had been persuaded to return for the summer from Philadelphia, where he taught regularly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The enthusiasm with which his classes were received surprised the University administration and led to the recognition that the arts should be accorded a more prominent place in the life of the University.

Russell T. Smith became the University’s first full-time teacher of art in 1936, but his stay was brief; in 1940 he left to become head of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Before he left, he persuaded John Volney Allcott to come from Hunter College to lead the department, which he did for the next 17 years. Allcott, with the support of the community group Friends of Person Hall, brought Mondrian’s Victory Boogie Woogie to campus in 1951, to considerable editorial comment in the state’s papers, and engaged major art world figures to speak. Allcott and his new colleague Professor Kenneth Ness, who had arrived in 1941, threw themselves into planning the presentation requested by the Ackland Trustees and prepared a forceful case proving that the University was more than ready for the challenge presented by Mr. Ackland’s will.

The state legislature was deeply involved, through the University, in the commitment to the Ackland Trust. But elsewhere it was taking another important step, one unprecedented in the American museum world, by establishing, at a propitious moment given the art market at the time, a fund of $1,000,000 to create an art collection for the proposed state art museum in Raleigh. When, in the late 1950s, the North Carolina Museum of Art and the Ackland were opened to the public within two years of each other, the state’s position among the country’s centers for the visual arts improved significantly.

Art image credits:

Original section of Person Hall on UNC-Chapel Hill’s campus. University Archives.

H. R. Weeks, of Eggers and Higgins, Architects, American, 20th century, The Ackland Art Museum at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (detail), 1954, graphite and color pencil, 13 x 23 11/16 in. (33 x 60.2 cm). Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Gift of John E. Larson, 83.17.1.