By Peter Nisbet, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, Ackland Art Museum.

When did the Ackland first acquire a work of art by an African American artist? This is the kind of query posed ever more frequently today, for reasons that are clear to all: however we individually define equity, diversity, and inclusivity, questions about the institution’s record and its adequacy will be increasingly urgent in this historical moment. And our recent activity in this field, such as the 2019 purchase of William E. Artis’s affecting and accomplished Head of a Boy, will also naturally prompt the search for antecedents, along with the search for an understanding of the varying roles played by accident and intention in making such acquisitions under particular circumstances.

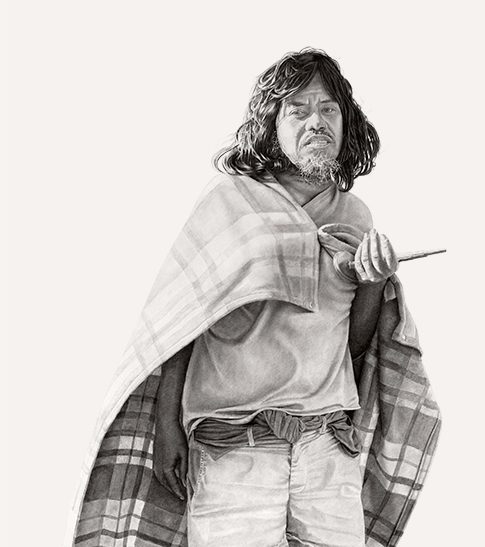

The Ackland’s first acquisition of work by a Black artist actually predates its founding in 1958 by a decade and a half. When the federal government distributed works from the Works Progress Administration program in the early 1940s, the Art Department’s Person Hall Art Gallery, a predecessor to the Ackland that opened in 1937, received, as part of a much larger allocation, two powerful etchings by the Philadelphia-based print maker, Dox Thrash (1893-1965), including Played Out. Such an acquisition, however welcome in retrospect, can seem almost inadvertent, as can other such works acquired as small parts of much larger gifts over the years. It was not until 1970 that the Ackland spent money on purchasing a work by a Black artist — an untitled lithograph by the Chicago-based sculptor Richard Howard Hunt. In the wake of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the 1970s seem to have seen a more conscious effort in the field, as shown by other additions to the collection that I’ve written about elsewhere.

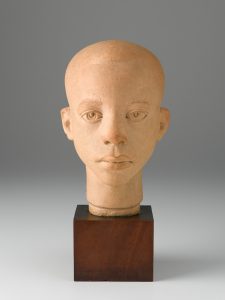

It was also in the early 1970s that our friends at the North Carolina Museum of Art purchased a sculpted head by Artis, a stimulating contrast to ours (G.73.7.1, illustrated). Even here, circumstances make for an intriguing story: Michael was actually purchased for the NCMA’s Mary Duke Biddle Gallery for the Blind, a pioneering and impressive effort begun in 1966 to create a touchable collection and exhibition program for blind and low vision visitors. The Gallery for the Blind hosted a one-person show of Artis from March to May 1973, from which the sculpture was purchased. It joined an amazingly wide range of objects, including many from non-Euro-American cultures on which this gallery could draw, until it was disbanded in 1983. Michael, unlike many other objects in that collection, was carried over into the permanent collection of the NCMA.

It was also in the early 1970s that our friends at the North Carolina Museum of Art purchased a sculpted head by Artis, a stimulating contrast to ours (G.73.7.1, illustrated). Even here, circumstances make for an intriguing story: Michael was actually purchased for the NCMA’s Mary Duke Biddle Gallery for the Blind, a pioneering and impressive effort begun in 1966 to create a touchable collection and exhibition program for blind and low vision visitors. The Gallery for the Blind hosted a one-person show of Artis from March to May 1973, from which the sculpture was purchased. It joined an amazingly wide range of objects, including many from non-Euro-American cultures on which this gallery could draw, until it was disbanded in 1983. Michael, unlike many other objects in that collection, was carried over into the permanent collection of the NCMA.

When the Ackland decided in 2019 to buy our artwork by Artis, our enthusiasm was also nurtured at the intersection of a number of more or less explicit preferences: we are consciously looking for more sculpture, especially American; for art with a regional connection (Artis was born in Washington, North Carolina); and for art by African American artists (see here for a discussion of a pair of acquisitions by living artist Willie Cole). It forms part of a much more intentional and wide-ranging project that can build on the promise of earlier acquisitions to offer a far richer and multi-faceted selection of art by Black artists of our time.

Art image credits:

William E. Artis, American, 1914-1977, Head of a Boy, c. 1935, low-fired clay on original wood base, head: 11 1/4 × 8 1/4 × 6 1/2 in. (28.6 × 21 × 16.5 cm). Charles and Isabel Eaton Trust, 2019.32. Photos by Mark Ostrander, courtesy of Conner-Rosenkranz, NY.

William E. Artis, Michael, mid-to-late 1940s, terracotta,10 1/4 x 6 x 8 in. (26.0 x 15.2 x 20.3 cm), North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, purchased with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), G.73.7.1