“Saphire” by Willie Cole

Close Looks: "Saphire" by Willie Cole

Click on the arrow below to listen to an audio description of the featured work. Click on the transcript button to read the description.

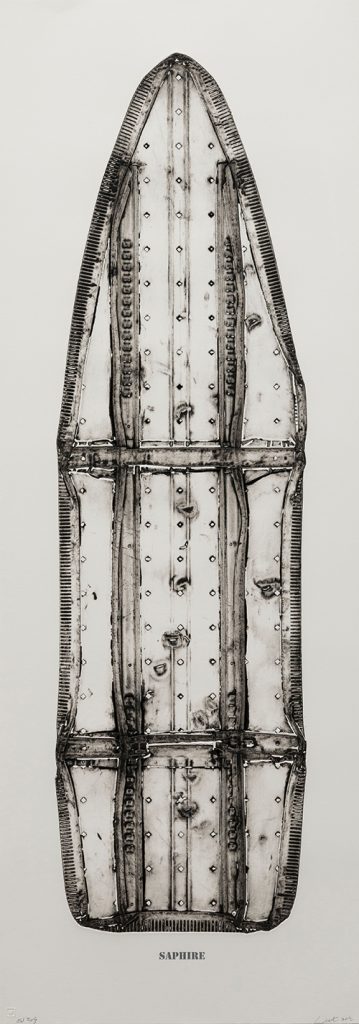

A vertical form is printed in black ink on a piece of thick white paper that is over six feet tall and just under two feet wide. The form extends to within a few inches of the top, bottom, and sides of the paper, filling the space without crowding it. Inside the form, there are areas of deep black ink, areas colored with shades of gray ranging from pale to charcoal, and a few areas of white paper, which look especially bright in contrast with the ink. Outside the form the paper is even in color and texture. Just below the form, in dark gray capital letters, is printed the word “Saphire.” At the bottom edge of the paper in pencil is the artist’s signature (Willie Cole), the date (2012), and the edition number of the print series (2 of 3).

The silhouette of the form is tall and narrow. The lower three-fifths of it is in the general shape of a rectangle while the upper portion resembles an elongated triangle. All around the silhouette, there is a border, about an inch thick, in a deep gray with a pattern of short parallel lines that are lighter in tone than the border they help to form. Just inside this border, there are small diamond shapes placed at regular intervals along the left and right side, about 16 on each side.

Inside the form, there is a framework of vertical and horizontal bars. Three vertical bars, about the same width as the border, are placed fairly evenly across the space so that they mark four vertically-oriented fields. The central bar runs the entire length of the form, with 22 of the small diamond-shapes at regular intervals from top to bottom. More diamond shapes appear in the two vertical fields that extend between the central bar and the ones that flank it on each side – 22 more diamond shapes in each of those fields – making a total of nearly 100 diamond shapes throughout the print.

The two flanking bars are slightly wider and darker than the central one, and they are similar in appearance to one another. Each of these two bars is divided into three vertical parts. Within these two flanking bars, there are clusters of squarish shapes, in groups of about a dozen. Each bar has two clusters of these shapes, one near the top of the form and one near the bottom.

Two horizontal bars run across the form, intersecting and overlapping the three vertical ones. In these horizontal bars it is more difficult to detect a shared, regular pattern, but in several places, along the external edge of these bars there is a thin line that runs parallel to the bars, and at the outer edges of each bar there is a circular hole in the surface of the ink.

In addition to the bars, diamonds, squares, and border of parallel lines, there are a few additional small shapes that are noticeable because they don’t line up with the

geometry and symmetry of the rest of the lines and shapes. They are more organic in shape, resembling ovals or half moons in some instances. It should also be noted that while the lines and shapes suggest an orderly, symmetrical structure, in most places in the print their outlines actually appear somewhat irregular, distorted, and slightly asymmetrical.

From a COVID-19-era physically distanced 6-feet away, the print has a striking presence, like a human-sized figure standing in a bilaterally symmetrical pose, graceful, poised, erect but not rigid. Examining it up close from both frontal and oblique points of view, the flat, black-and-white image becomes more nuanced and its three-dimensional qualities emerge.

The exterior boundary between the image and the surrounding paper is crisp and clean – a sharp contrast between black ink and white paper – but inside numerous shades of gray are visible. In some sections, smudges of ink look like atmospheric shading. Light scratches seem to fade in comparison with the deep, dark pools of ink nearby. The pools of ink reflect light, shining like obsidian; in places they are thick enough to cast a shadow on the surface of the paper. In many places, the printing plate pressed so firmly into the paper that the paper projects noticeably, for example along the edges of the horizontal bars. The glossy ink and dense paper evoke the sense of touch and call attention to the texture of the print’s surface.

What Do You See?

For me, Saphire evokes the past. I am immediately struck by the sepia-like tone of the work; it feels incredibly vintage. The contrast of light and dark direct my attention to the lines that appear jagged and uneven, a reflection of accumulated wear produced by age and the passage of time.

Stark and quite simple in appearance, this work projects a quiet power that pulls at me ever so slightly, in a way that slowly builds and intensifies. Only upon learning that the artist, Willie Cole set out to honor the women in his family — many of them domestic workers — do I begin to focus on the object itself. To capture the lives and labors of great-grandmothers, grandmothers, aunts and their friends, Cole calls our attention to an ironing board that was synonymous with domestic work in the twentieth century. The jagged lines now assume heightened significance and call to mind the exhaustive labor black women have endured. Cole manages to reach beyond his family, too. The board assumes an outsized presence that completely dominates and overwhelms the print. From this vantage point the shape of the board easily resembles a boat and the holes appear to be people crowded in the space. The likeness invokes the transatlantic slave trade, turning the domestic labor of black women into a potent symbol of black suffering.

– Jerma A. Jackson is an associate professor in the department of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Willie Cole, American, born 1955, Saphire, from The Beauties, 2012, intaglio and relief on paper, 63 1/2 × 22 1/2 in. (161.3 × 57.2 cm). Ackland Fund, 2016.7.5. ©2012 Willie Cole. Courtesy of Alexander and Bonin, New York.

On the one hand, Willie Cole’s Saphire does exactly what great prints tend to do: offer us a glimpse of the endless possibilities of a deep and intriguing discipline. Yet, Saphire (as with Cole’s other Beauties) pushes even beyond that mark by revealing the dignity and mysticism of an otherwise humble, domestic object. Although hammered into low relief, inked, and printed as a two-dimensional image, the ironing board’s objectness advances up and off the page. It continues to make its case as something to be considered by way of its inherent beauty and continual offering of complexity and nuance. Like Cole, I have also been shaped by a dense constellation of strong Black women both in my family and

cultural history. The titles of his Beauties read like a biographical novel or family tree that mirrors my own origin story. However, my kinship with Cole’s Beauties extends beyond a shared ethnicity. The artist has constructed a relationship between processes, title, and graphicness that taps into a universal desire to connect to something that sight and intellect cannot fully account for.

– Stacy Lynn Waddell is a visual artist and UNC-Chapel Hill MFA alumna whose multi-part print A Midnight Race Between A Butterfly And An Eclipse is also a part of the Ackland’s permanent collection.

On the first look, this piece appears transparent or crystalline; it made me think of a Coke bottle. My next thought was of the sketches of the ships used on the transatlantic slave trade. This piece feels both empty and yet heavy.

I asked my three-year old daughter what she saw. She said she saw “black and white and buttons.” She thought Saphire looked like a “mommy dress.” An extremely astute observation, I realized after learning that the series this belongs to represents women in his family.

I feel much closer to the piece because some of my cherished family members were domestic workers and dressmakers. I’m fascinated that the use of a simple household item such as an ironing board could connect the slave ship and the history of Black women as cleaners for white households. I was initially confused by the title but knowing that it represents a specific woman and elevates her to a work of art gives the piece beauty beyond merely being about Black pain and the misuse of Black bodies.

– Deandra Scott Hill has been an educator for fifteen years in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, Durham Public Schools, and Duke TIP, and she is also on the Board of Directors for Her Spark.

- What words come to mind when you look at this print? What do you think it looks like?

- Describe the marks and patterns you see on the print.

- Willie Cole hammered, flattened and pressed ironing boards to be a few millimeters thick, so that he could use them as printing plates for his series The Beauties. Where can you find evidence of this process?

- Each print in the series is given the name of a woman, real or imagined. How does the act of naming affect the print’s meaning?

- If Cole’s aim is to honor the lives of African American women who worked as domestics in the American South during the era of Jim Crow in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in what ways might his process of making these prints resonate with their lives?

• Read an interview with Lauren Turner, Assistant Curator of the Collection, about the acquisition of this print.

• Learn more about Willie Cole and his work. Explore the artist’s website. Watch an episode of State of the Arts with Willie Cole.

• Learn more about studio where Willie Cole produced his prints. Visit The Highpoint Center for Printmaking website.

• View a conversation with artist Willie Cole and Cole Rogers, artistic director of Highpoint Center for Printmaking, about The Beauties, held by the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University.

Close Looks at Cocktail Hour: Willie Cole’s Saphire

November 11, 2020 | 5:00 p.m.

Join the Ackland’s Object Based Teaching Fellow, Erin Dickey, for an informal conversation focused on one work of art from the Ackland’s new Close Looks online installation. Plan to look closely and think collectively—and bring a drink of your choosing.

On November 11, we’ll look at Willie Cole’s Saphire. Registration is limited. RSVP below! After RSVPing, you will receive a separate email with the Zoom link before the virtual tour.

Free. Registration required. Click here to register.

Art for Lunch: The “Can We Talk About Race?” Initiative

November 18, 2020 | 12:00 p.m.-1:00 p.m.

Featuring Diana Dayal and Bria Godley (UNC School of Medicine) and Elizabeth Manekin (Ackland Head of University Programs and Academic Projects)

During this virtual Art for Lunch, held on November 18, 2020, the conversation focused on the “Can We Talk About Race?” initiative of the Ackland and UNC’s School of Medicine. The initiative, now in it’s third year, uses artwork made by contemporary Black artists as a catalyst to discuss race and racial inequity in medicine. Click the video player below to watch the recording!