“Entering Zig’s Indian Reservation” by Zig Jackson

Close Looks: "Entering Zig's Indian Reservation" by Zig Jackson

Click on the arrow below to listen to an audio description of the featured work. Click on the transcript button to read the description.

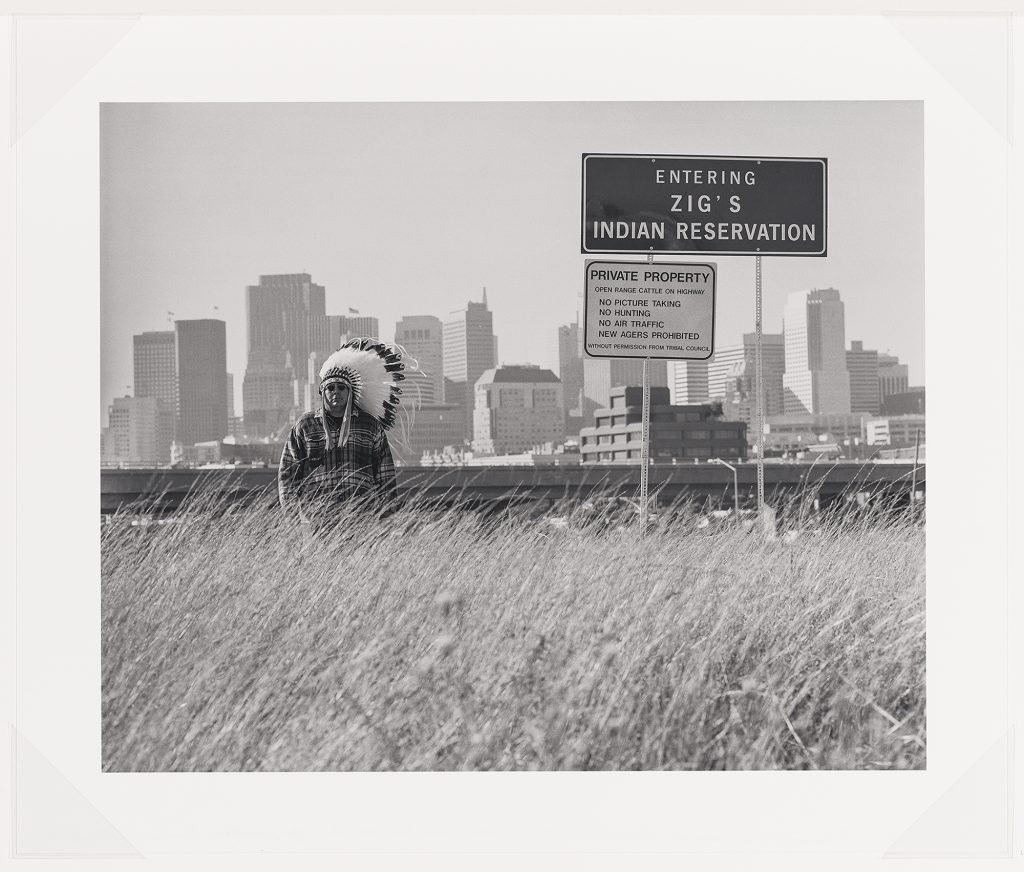

This horizontal format, black-and-white photograph is about twenty inches high and twenty-four inches wide. Before a city skyline, in an expanse of tall grass, a man stands in the scene’s left half. In its right half are two large metal signs.

The scene is divided in half horizontally by an elevated highway. In the half of the composition above the line formed by the highway (which can also be described as the physical space most distant from the viewer’s eye), the image is filled with urban buildings. The buildings — most of them skyscrapers — extend from the left edge of the scene to the right. Above (and behind) the roof lines, the sky is visible, occupying about half of the space in this upper portion of the composition.

In the portion of the composition below (and in front of) the line of the highway, the image is filled with tall grass that continues beyond the left and right edges of the photograph. The blades of grass lean to the right, suggesting a prevailing wind from somewhere to the left of the scene.

The standing man is the photographer of this work, Zig Jackson. He is only visible from the waist up with the tall grass concealing his lower body. He stands facing the viewer wearing a plaid flannel shirt, dark sunglasses, and a feather headdress. The wind current appears to be blowing the feathers (as it does the grass) to the right, so that the headdress is positioned asymmetrically on the artist’s head.

If there were a vertical line dividing the photograph’s composition in half, Jackson’s location in the left half would be almost mirrored by the location of the two metal signs in the right half. The lower part of the metal signs’ posts are hidden by the waving grass, just as Jackson’s legs are. The larger of the two metal signs is a horizontally oriented rectangle supported by both of the metal sign posts. It is placed above the smaller, more squarish sign that is supported by just the left-hand metal signpost.

The larger sign has white capital letters on a dark background. It reads: ENTERING ZIG’S INDIAN RESERVATION. ENTERING is on the top line, ZIG’S is on the middle line, and INDIAN RESERVATION is on the lower line. Around the dark background there are two thin borders, the inner one is white and the outer one dark. In the lower left quadrant of this sign the uniform color of the sign’s background is interrupted by what appears to be a reflection of something.

The smaller sign features dark capital letters on a white background, the text divided into seven lines. The top line, in the largest letters is: PRIVATE PROPERTY. The next line, in smaller letters is: OPEN RANGE CATTLE ON HIGHWAY. The next four lines, in letters smaller than the top line and larger than the second, read: NO PICTURE TAKING; NO HUNTING; NO AIR TRAFFIC; and NEW AGERS PROHIBITED.

The seventh line is also in small letters: WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM TRIBAL COUNCIL. There is a dark linear border around this second sign, with curved, rather than angular corners.

The photograph’s focus is sharpest and the dark shades darkest in the middle ground, where Jackson, the signage, and the blades of grass closest to them appear. The elevated highway is the next sharpest. The softest focus and palest shades appear at the lower edge, where the grass is closest to the viewer, and in the architecture most distant from the viewer, seemingly dissolving into the bright light of the sky.

Throughout the composition horizontal and vertical elements create a kind of visual grid that gives structure to the image and that creates an interesting contrast with the bending and curving areas, like the grass, the feathers, the outline of Jackson’s head and shoulders and, atop some of the buildings, fluttering flags. Vertical elements include: Jackson’s stance; the sign posts; the architecture. Horizontals include: the highway, the format of the larger sign, and the format of the photograph. The plaid pattern on Jackson’s shirt echoes this network of horizontals and verticals and resonates with the patterns formed by windows on the buildings in the background, some of which resemble the pattern of holes in the metal signposts.

I suspect that anyone who grew up in North America can recognize that the artist is manipulating stereotypes and juxtapositions. That much we can all see — the real question is what meaning does one take from that manipulation.

The image is certainly playful. It is important to recognize and appreciate this humor. But those who merely “knowingly” chuckle at Zig’s Reservation or the sign may want to reconsider if they are really in on the joke.

What I see is a person claiming his own space in the world. Certainly this evokes “take back the land” movements, but it is deeply personal as well. It is someone making space to be comfortable in both a headdress and a flannel shirt. The artist also reverses the “vanishing Indian” trope by focusing the image on himself and the sign while leaving the city skyline obscured. But I am most struck by the ambiguity of where Zig’s Reservation begins and ends. Just where is Zig’s Reservation? What might your first impression reveal about how you conceptualize the Indigenous world?

– Keith Richotte is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and an Associate Justice on the Turtle Mountain Tribal Court of Appeal. He is also an associate professor of American Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Zig Jackson, Native American, born 1957, Entering Zig’s Indian Reservation, China Basin, San Francisco, CA, 1997, archival pigment print, 20 3/16 × 23 15/16 in. (51.3 × 60.8 cm). Ackland Fund, 2019.9.3. © Zig Jackson, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara.

I am first drawn to the sign reading “Entering Zig’s Indian Reservation,” which is the tallest object in the photo. It looks authoritative — like something you see on a highway, in a national park, or in a public space. Despite its authority, a reflection in the sign makes me question if it was a part of the landscape or added later. My eye then darts to see a self-portrait of the artist with a Native American headdress on and dark sunglasses obscuring his eyes, which makes it difficult to decipher if he is looking at us. His expression seems stoic. The feathers of his headdress bend in the same direction as the tall grass while Zig, the sign, and the buildings stand upright. The photograph is divided by a horizontal

line, which looks like a highway to me, and separates the grassy undeveloped side closer to us from the crowded but muted cityscape of San Francisco behind Zig. I see a body in dialogue with its landscape, asking to be seen, but swallowed by buildings and grass.

– Julianne Miao is the Ackland’s 2021 Joan and Robert Huntley Scholar and a master’s student in Art History at UNC-Chapel Hill, who spent the summer studying the photography collections of the North Carolina Museum of Art and the Ackland.

To me this is a powerful statement of reclaiming sovereignty. The artist, Zig Jackson, seems to be saying a lot of the kinds of things that a lot of indigenous people would like to say. The anti-new-ager sentiment is extremely familiar, but few of us get to really put it out there like this in our day-to-day lives for fear of censure by non-natives. I think also what strikes me is the concept of roping off a particular designated area of land and how radical that seems when a native person does it rather than a settler. Decolonizing work like this — work toward reclamation — is often subtle, and slow, and the concept of a sign just saying all these things outright is rather inspiring. On the other hand, I hate that I had to wonder if the artist was a citizen of the nations he claims — a cursory Google search seems to indicate that he is enrolled — but the preponderance of people making claims of native identity that cannot be substantiated (especially in academic circles) is alarming and sad. I think there is a tension that is inherent whenever I see

native art like this between being proud and inspired, and being eternally leery of claims until I know who someone’s people are and know that they also claim that person. Off the cuff, I also sort of hate that I wonder whether this sign is real and whether its claims about sovereignty are truly honored— is this an empty gesture, or did someone truly win back the land that was stolen from indigenous people? The fact that I need to ask that question is, in itself, a mark of settler colonialism’s impact on native perspectives. What if we lived in a world where things like this were just what they were? And how joyful would it be if we could see this and say “yes; this is what is supposed to come to pass. Thank you.”

– Dr. Ben Frey is an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and assistant professor of American Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The year is 1997 and if the title is to be believed, the artist Zig Jackson stares defiantly into the camera for a self-portrait on his own reservation. The frame is split decisively in half by the dark line of a raised interstate that divides the modern skyline from the overgrown grasses of the reservation. So close to “civilization” and yet this land retains some wildness. This is a political statement to be sure, but also has some rewarding ironies. The subject wears a traditional headdress with modern sunglasses. The reservation is not named for the three tribes to which he belongs, but is Zig’s. And

the second sign is filled with warnings, Cattle on the road, and only picture taking, hunting and flying with permission of the tribal council. And the delightful “new agers prohibited” — from what? The message is ultimately clear, “This is my place, and I make the rules.”

– Bryce Lankard is a lifelong photographer, an instructor at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies and the director of the Click! Photography Festival.

- Describe the landscape. What relationships can you draw between the foreground, or the area representing the “front” of the image, and the city skyline in the background?

- Describe the figure, his body language, and attire. What parallels can you draw between those descriptions and the landscape?

- This is part of a series of photographs that depicts the artist in front of a range of landscapes and monuments, titled Entering Zig’s Indian Reservation. What ideas does that spark about American Indians, past and present, and land use in the United States?

- JOIN US for an Artist Conversation with Zig Jackson on Wednesday, October 27, 2021 at 1:00 p.m. Eastern, held via Zoom.

- Learn more about Entering Zig’s Indian Reservation, China Basin, San Francisco, CA in the Ackland’s About the Art guide.

- Visit the artist’s website.

- Zig Jackson is a member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes. Visit the nation’s website to learn more about the Three Affiliated Tribes.

- The UNC American Indian Center is the front door to the University for American Indian students and communities. Visit their website for information on events, educational resources, and more.

- Read about how UNC-Chapel Hill is exploring Carolina’s historical and current connections to American Indians in The Well.

I have always admired Zig Jackson for years has great personality great to get along with, griugh his photography is where I gain my own interest in photography.