By Peter Nisbet, Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, Ackland Art Museum.

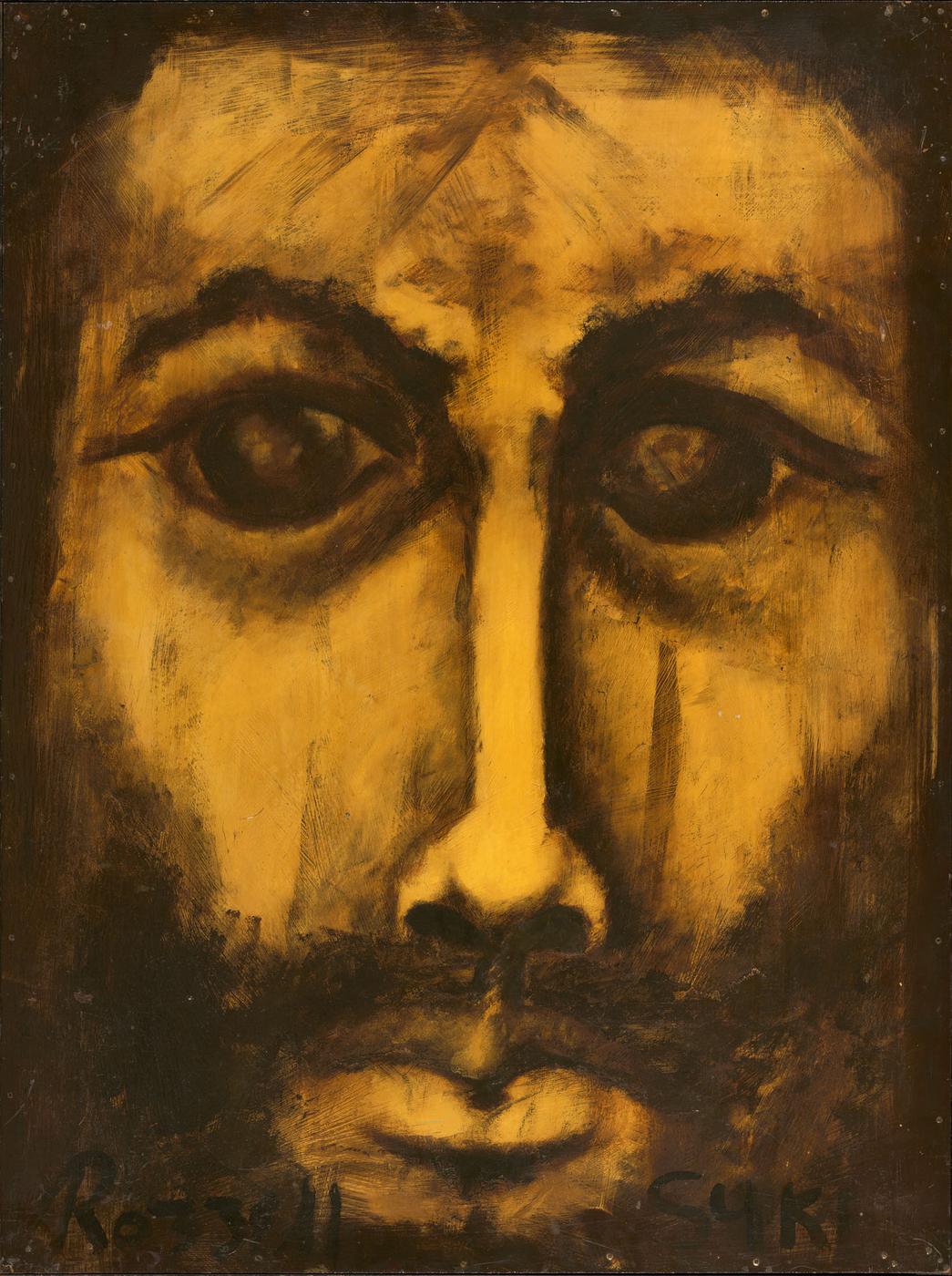

On 18 July 1972, then Ackland director Professor Joseph Sloane asked the Museum’s Advisory Board (a small committee of faculty and university administrators) for “permission to purchase a painting by a California black artist for $200,” which he described as “in between folk art and fine art.” This work turns out to have been a large painting by the African American artist Rozzell Sykes (1931-1995), illustrated here. Sykes is not well known today (only one or two works may be in institutional collections), though he seems in the 1960s to have had paintings commissioned and published by Life Magazine and shown in London (maybe at the Tate), in New York (at the Martha Jackson Gallery) and several other places. Whatever the shape of his career, this painting is a powerful one and the story around its acquisition is a good one.

In June 1972, Sloane had visited St. Elmo Village, an extraordinary project in the Mid-City neighborhood of Los Angeles. A couple of years earlier, Sykes had led five other artists, including some relatives, in taking over a court of ten houses and garages to create “an environment in which art will become an integral part of everyday life” (in the words of a 1970 newspaper article). “Every Sunday, the artists display their works outside, on the walls of the houses, on the front lawns, over the windows – anywhere they can drive a nail and hang a painting or put a sculpture.” In late July, Sloane wrote to Sykes about his visit and having seen the painting he ended up buying: “It was large face in brown and black, and hung on the side wall of the building at the end of the row of garages.” Sloane says Sykes had quoted a price of $150, but he offered $200 (as he felt the Village “could use a little money”). With packing and shipping, the Ackland paid $250.

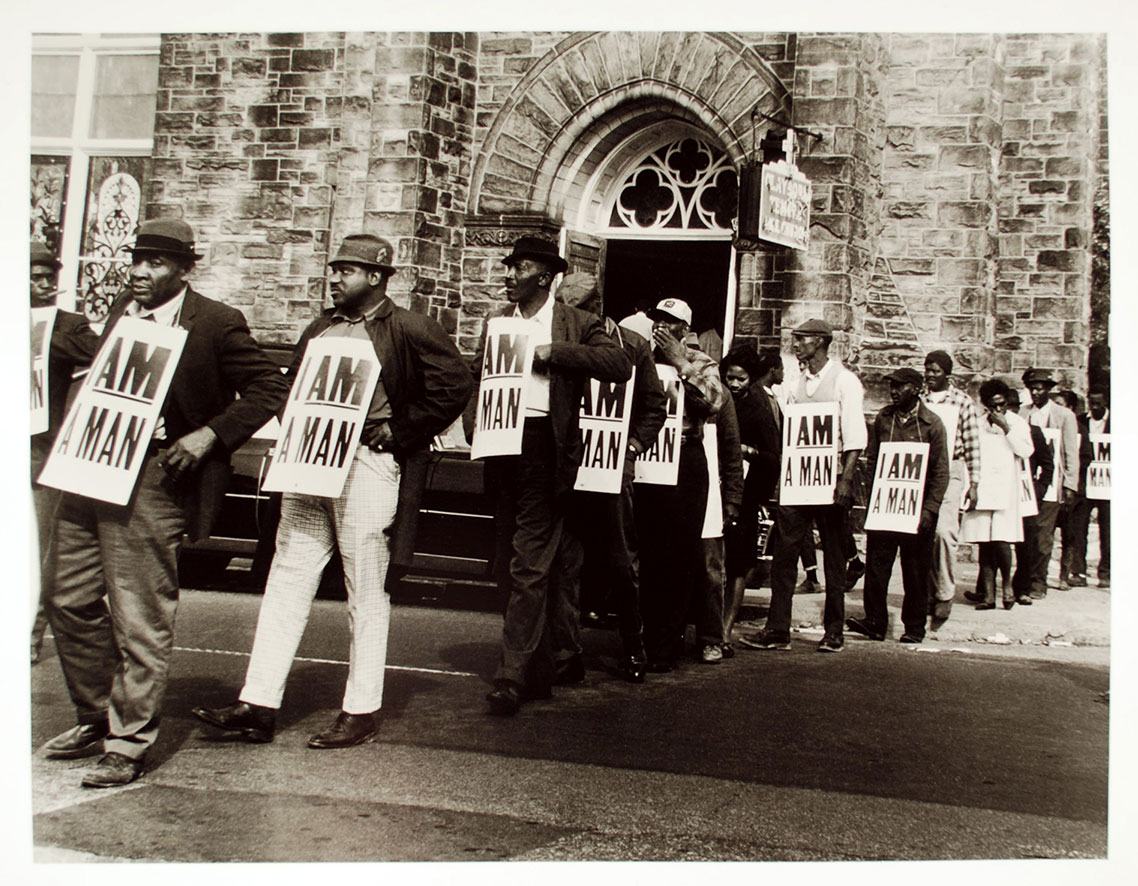

Was this a surprising purchase? For those art historically inclined, it is noteworthy that at the very same moment Sloane was buying not only a lithograph (72.40.1) by the earlier French artist Georges Rouault (1871-1958), whose expressive, monochrome, monumental style matches Sykes’ approach, but also the first print made by Sam Gilliam (b. 1933) (72.45.1), now a towering figure in contemporary African American art and experimental abstraction. The Sykes acquisition lies at the intersection of those interests. And there may be a broader institutional context, too. The Ackland’s major fall exhibition in 1972 was entitled Some American History. Circulated by the Institute for the Arts at Rice University at Houston (and in effect a project of the pioneering art patrons John and Dominque de Menil), this bold and important multi-media exhibition presented searing and pointed work on African American themes by white Jewish artist Larry Rivers (1923-2002), together with works by six African American and diaspora artists, such as Frank Bowling (b. 1936), William T. Williams (b. 1942), and Peter Bradley (b. 1940). Rivers’ montages and assemblages directly and unambiguously addressed such subjects as lynching, slavery, and Black Power.

Was this moment in 1972 (and others like it in the course of the Ackland’s history) simply tokenism? Or evidence of a deeper and more extensive inclusivity? The answer, I suppose, will depend on much more research and I leave the judgement to those more comfortable with moral assessments of an institution’s past. For me, the tremendous significance of what I’m describing lies more in how it contributes to making available a usable tradition on which to build any current engagement with Black art and racial justice. And one key part of that legacy is the presence in the permanent collection of Sykes’ painting. Even though it may only have been shown twice during its time at the Ackland (both times in the 1970s, it seems), its slumbering potential has always been there. And, as the Ackland prepares to focus on using art to engage with vitally important social issues at this crucial juncture, the painting can emerge and help. It will be on view when we re-open. It may even promote the sentiment that the artist inscribed on the back: “I, Rozzell Sykes, of St. Elmo Village say then be of care to have a nice forever.”

St. Elmo Village is still functioning. For more information, including some history, click here.

Research on the Ackland’s presentation of Some American History is continuing. For one description of the exhibition and its catalogue, click here. An installation view from the Houston presentation, and some commentary on the project in the context of the de Menils’ activities, is available here.

Art image credit:

Rozzell Sykes, American, 1931-1995, Head of a Man (The Face of Evil), c. 1972, oil on composition board, 36 x 48 in. (91.4 x 121.9 cm). Ackland Fund, 72.44.1.

Thanks for this article! I just happen to be putting together a PowerPoint for my Docent members at the Brooks Museum of Art here in Memphis, TN where I live, on the life work of Rozzell Sykes. His collection is too vast to include in a mere PowerPoint but I have been trying for years to get my dear friend’s work shown at the Brooks to no avail, even though the former curator said she was a fan of folk art and self-taught artist.

Yes, Rozzell said his art could, perhaps, be in a museum somewhere in the world, but living his day to day life wouldn’t allow for him to know where all of his ‘children’ landed. When Rozzell passed in 1994, a few days before his birthday, he left a void in all of our hearts. He was truly my best friend.

Glad I came upon this article. I love what Mr. Nisbet wrote about one of my favorite people. I miss him daily.