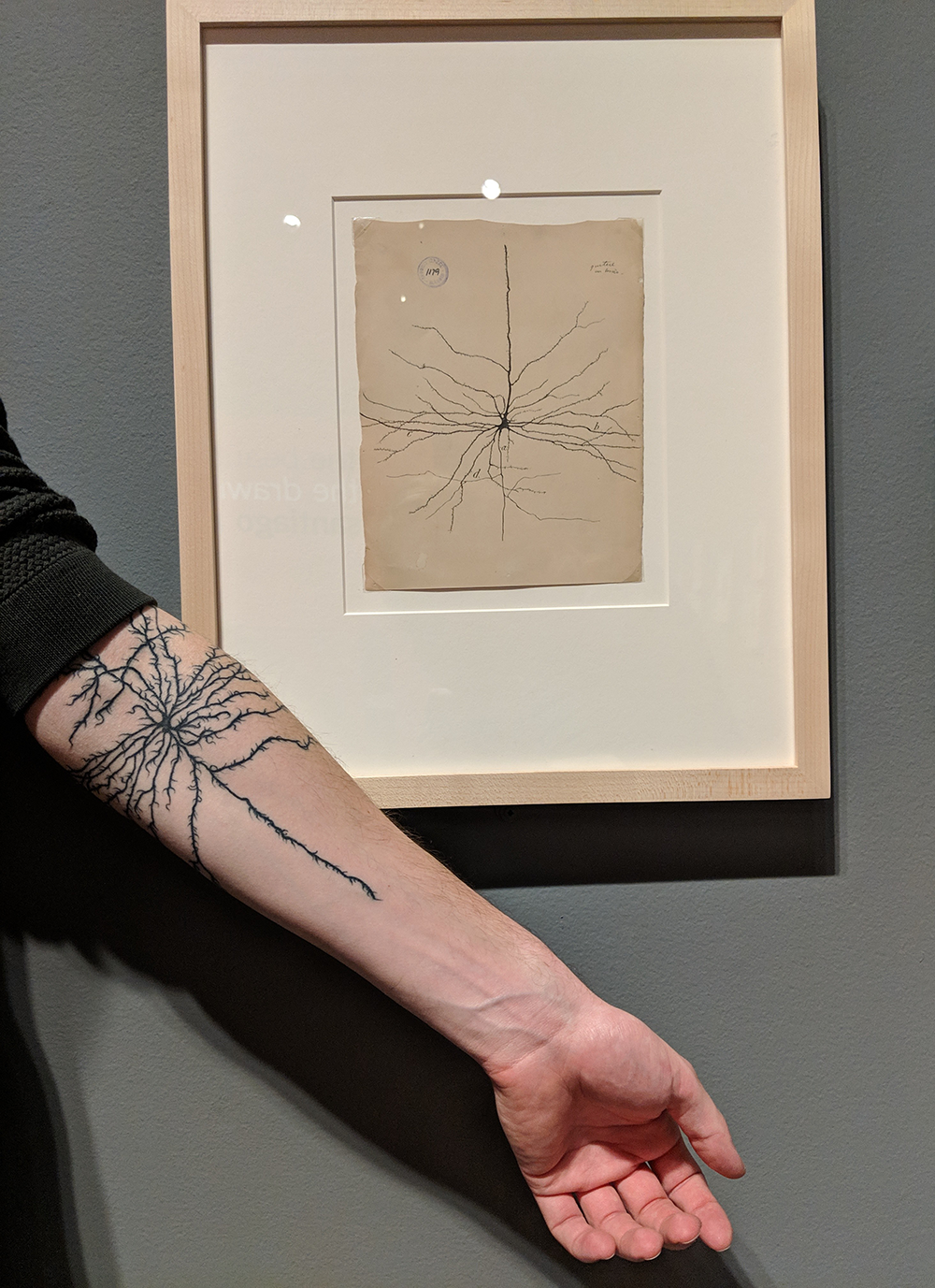

Vincent Boudreau, recently turned Dr. Vincent Boudreau, is a graduate student in Cell Biology at UNC. A rumor reached the Ackland that Boudreau had a tattoo of a Cajal drawing on his arm, so naturally we wanted to find out more. The Ackland’s Ariel Fielding interviewed this fellow Canadian-North Carolinian shortly before the closing of The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

You are one of two visitors to The Beautiful Brain whom I know of with a Cajal tattoo. I understand that, by sheer coincidence, you heard The Beautiful Brain was coming to the Ackland right after you had decided to get your tattoo. Tell me about your work at UNC and why Cajal is important to you.

As a cell biologist, I’ve always been very taken by these nineteenth century/turn-of-the-century scientists who illustrated their findings. It’s always seemed a cross between science and art in some way. I’ve always been inspired by that. Santiago Ramón y Cajal is not the only one; I’ve really loved illustrations by Ernst Haeckel and several others who are well known for that kind of work. The inspiration for the tattoo that I got is someone very close to me, my daughter, who has a brain condition. Obviously that’s a difficult situation, but one thing that really struck me about trying to learn about the molecular and cellular components of that condition, and also the potential outcomes, was both how little we know about how the brain works, and how mysterious it is as an organ. Santiago Ramón y Cajal—we can see it in the exhibit—shows how complex different types of cells are in the brain, and how complex the connections between cells are. The inspiration for my tattoo comes from the artistic component of his work, his ability to delicately illustrate things that are so complex, as well as the mysteries of how the brain works.

Why this particular image, The pyramidal neuron of the cerebral cortex?

Getting a tattoo—there are several components that go into it. One of the main things is, how easy is it to put on skin? Images or drawings that have small, delicate lines with very high contrast are perfect. That’s one of the components of his images. I think that drawing in particular is one of his illustrations that, to me, is most aesthetically pleasing. It really illustrates how complex that particular type of neuron can be while being simple enough to put into tattoo form.

It’s interesting what you said about your daughter; I just learned that Wilder Penfield, a neurologist and neurosurgeon who studied with Cajal, was deeply interested in solving the mystery of epilepsy because his sister had the disease. I don’t know what you’d call that kind of impetus, but I wonder how common it is among scientists.

I’ve been in science for the better part of ten years, and I’ve found my own inspirations. I’m very interested in the intersection of science and art. The way that scientists operate is very similar to the way that many artists operate, in the way they pursue their work and in what inspires them. I’ve found inspiration in my work, but I have thought about the complexities of the nervous system and the complexities of neuroscience, and considered changing course, especially with the situation with my daughter. The question of impetus is very interesting.

Do you have an artistic practice yourself?

I don’t, but my partner Natalie is a curator for Kalisher in Carrboro. We’ve hosted a conference here at RTP [Research Triangle Park] on the boundaries between art and science. I think there are a lot of parallels in the ways that artists and scientists work and think, and also their practice, their craft. For scientists and artists, their work is something that comes to be with hours and hours of work, with craftsmanship, and with dedication.

Tell me about your scientific work.

My Ph.D. has been on, broadly, cell division, and when cells divide, regardless of the context in which they divide, the nucleus of the cell needs to be assembled every time. This happens especially in development almost a trillion times to form all the cells of the body. I’ve been very interested in how the nucleus, which houses all the genetic material of the cell, comes to be and how it’s physically built. That’s more or less been the cornerstone of my thesis, and why the regulation of the shape and size of the nucleus after cell division is really critical in maintaining healthy cells. We know that that kind of process goes wrong in disease states, especially in cancer.

So you’re looking also at what can go wrong in cell division and what factors can influence that?

Exactly. This is another thing that has drawn me to Santiago Ramón y Cajal and other turn-of-the-century scientists: I’ve spent most of my time doing microscopy, watching cells behave and carry out their functions. The microscopy that we do today is very different from the microscopy that was done in Cajal’s time, and I think that’s illustrated in the exhibit, in having a contemporary component. It’s always something that’s been striking in this kind of work: we interpret our images and our microscopy in a similar way, whether that’s in a more quantitative fashion or in deciding what we’re looking at. Santiago Ramon y Cajal had to interpret what he saw under the microscope to illustrate exactly the point that he was trying to make. In cell biology today, the importance of interpreting what we see under the microscope is no less than it was for Cajal.