CLOSE LOOKS: "NEXT GENERATION II" BY ALLAN C. HOUSER

Click on the arrow below to listen to an audio description of the featured work. Click on the transcript button to read the description.

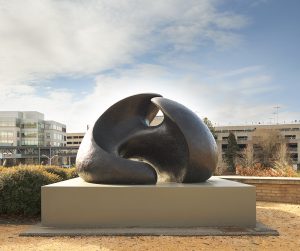

The abstract bronze sculpture called Next Generation II, made by Allan C. Houser, is installed in the UNC Hospitals complex in Chapel Hill. In the context of the hospital buildings, which are as many as eight (or more) stories tall, the artwork’s height — just over five feet — gives it a very noticeable human scale. Although it is an abstract sculpture, its biomorphic forms call to mind certain aspects of human bodies.

Those human associations are most evident from one side of the low, square pedestal that supports Next Generation II — the side viewers see when facing south, with the Children’s and Women’s Hospitals behind — therefore the northern side of the sculpture. From the other sides the forms still appear biomorphic, but not as much like bodies. More about the forms and their relationships to each other later.

The sculpture’s environment reinforces the idea that its northern side is the principal view. The low, square pedestal that supports the sculpture is between two and three feet high, painted gray, and it sits on an unpainted concrete lip, also square, also gray, though a slightly different shade of gray. There is a low brick wall that curves around the pedestal’s perimeter, embracing it along the eastern and southern sides. Low, evergreen bushes are planted along these same two sides between the wall and the pedestal. The northern and western sides of the sculpture, then, are the ones most accessible to viewers. There is a narrow space along the southern side that allows an agile viewer to sidle along the sculpture and get a close-up view, but on the eastern side the wall is too close to the pedestal to navigate between them.

Furthermore, when facing Next Generation II’s northern side (looking south), a spectator can look down and see two plaques on the concrete lip at the right corner. One plaque identifies the artist and his tribal affiliation (Allan C. Houser, Chiricahua Apache), the sculpture’s title (Next Generation II), medium and date (bronze, 1989) and asserts that it belongs to the Ackland Art Museum, a gift of Dr. Hugh A. McAllister Jr., M.D. Just to the left of this plaque is another, larger one, with a quotation about the sculpture by McAllister. More about that later — after more about the forms and their relationships to each other.

With a five-foot height at its center and an eight-foot width at its base, the sculpture has a low center of gravity. Looking at it from this principal viewpoint, Next Generation II’s structure is, in general, solid on the left and right sides, with two open areas in the middle, one above the other. Its silhouette, like the forms that make it up, is more of a biomorphic shape than a geometric one. I’ll begin describing the solid form on the sculpture’s left side, then the solid form on its right side, and then the combination of solid and open areas in the middle.

The solid form at our left, while clearly an abstract form, reads to me almost like a profile of an abstracted human figure, seated on the ground (that is, on the pedestal) and leaning forward to the solid form at the right. Maybe it seems this way because of the sculpture’s overall human scale. The upper two thirds of this abstracted human form might then be the figure’s back, shoulders, neck, and head, arcing in a long, continuous, elegant curve. The lower third of the form then, perhaps, represents the figure’s legs, in a kneeling position. Shifting my position slightly to the right and looking at a downward angle into the sculpture’s lower open space, I notice the rounded end of the knee-like form, making it seem even more to me like an abstracted knee.

Taking this analogy further, the right side of the abstract figure’s body is marked by an edge that divides the convex form that describes its back from the concave area that corresponds to the figure’s front. The edge dividing concave and convex, figure’s back and front, narrows the concave form as it curves gracefully upward. At the upper part, then, the bronze form might be the figure’s head, although its contour more closely resembles the shape of a human tongue.

The solid form on the right side as we face the sculpture is, like the form on the left, convex on the outside, concave on the inside, and curved as though leaning toward its counterpart on the left. This form is constructed more simply — no appendages of any kind are visible, so that its more evenly curved silhouette is what’s most evident. Also, it is a little smaller than the form on the left side. At its upper edge we might also read the narrowed bronze form as the smaller figure’s head. It leans toward the “head” of the other figure, and nearly joins it a few inches below.

Between the forms at the left and right sides of Next Generation II, inset from their outer edges, by probably a foot or two and relatively equidistant from the top and bottom of the sculpture, there is a bronze form that connects them. Again, the connector’s shape is more organic than geometric. The open space between the connector and the figures’ “heads” resembles a squat teardrop shape, and the open space below the connector is somewhat oval. The connector could be described as looking like the neck of a human figure lying down, seen from the side. But given the way we’ve been talking about the left- and right-side forms, it might make more sense to describe the connector as resembling arms reaching out to embrace.

Taking a closer look, the upper contour of each figure’s head also suggests a connection. The smaller figure’s has two rounded points that nearly touch the larger figure’s single rounded point, suggesting that if they were just a little bit closer to each other they’d fit each other perfectly, connecting the two sides of the sculpture.

From the pedestal’s western side, looking east, most of what is visible is the rounded-but-not-round back of the smaller figure, with a glimpse of the larger figure’s tongue-shaped head and the side of its upper torso that isn’t visible from the front.

Squeezed into the narrow space between the southern side and the wall and bushes, there is a better view of the nearly-touching heads, as well as two more curved, biomorphic shapes that weren’t visible from the front. At the lower edge of the smaller figure, there is a form that might be read as the figure’s foot. This form, while convex at the bottom, includes a concave space of a size and proportion that resembles a sort of hammock of a size that could accommodate an adult. If someone did curl up in that concave, hammock-like area, they would find themselves leaning gently against the smaller figure’s body, encircled and protected by the bronze that makes up its back.

The other curved shape visible only from this side is at the lower, outer edge of the larger figure. The rounded, sturdy form of a foot firmly planted on the pedestal supports another sturdy, rounded form that reads like a leg, bent in the process of kneeling or standing up.

The surface of the sculpture is a warm, grayish bronze color all over, but depending on light, shadow, and reflections it looks grayer from some perspectives and browner from others. Throughout the surface there are patches of pale green patina on the bronze. There are several different kinds of marks on the surface of the bronze: some appear random and others are patterned, as though made by tools. The light interplays with the marks, the patina, the concave and convex forms, and the bronze, making Next Generation II more legible than it might have been if the surfaces were even, smooth, and polished.

The quotation by Dr. McAllister mentioned earlier reads:

Next Generation II is symbolic of the love, values, and knowledge passed from one generation to the next. This abstract representation will be interpreted by each of us differently, whether that interpretation includes a parent and child, teacher and student, physician and patient, minister and congregant, or simply two friends. But this important sculpture reminds all of us of our duty to pass the virtues we hold dear to the next generation.

I see an embrace. A mother, wearing a blanket wrapped around her shoulders, extends her arms out to envelop her little one in warmth and comfort. The little one’s arms reach high—in need, in excitement, in aching relief—to clasp her neck. Joined, they are two halves made whole. They are their own and yet, also each other’s. I see the nurturing, strong Native women in paintings and sketches my own mother collects on her walls at home, and in the many exhibits she took me and my sister to view growing up. I see lines and light and artistry I would not be able to see without the guidance she shared all those afternoons we spent together in the galleries of D.C.

- Marissa Carmi (Oneida Nation of Wisconsin) is the Associate Director of the American Indian Center and PhD candidate in American Indian and Indigenous Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Allan C. Houser, Chiricahua Apache, 1914-1994, Next Generation II, 1989, bronze, sculpture: 61 x 92 x 74 in., 1500 lb. (154.9 x 233.7 x 188 cm, 680.39554 kg). Gift of Hugh A. McAllister Jr., MD ’66 in honor of his father Hugh A. McAllister Sr., MD ’35, 2012.3. © Chiinde LLC (a Houser/ Haozous family corporation).

Art asks us to pause, to breathe, to look, to ponder and then, to walk away holding a memory, however fleeting, of a moment in which the world grew still. This happens in the galleries at the Ackland Art Museum every day. I have seen it. But I have also seen this mystery with what is called public art. Public art is set into the wider world, with the context of changing light and shadow, sound and silence. Nevertheless, a stillness comes if we will pause.

Next Generation II is a remarkably quiet work of art. The scale is human – five feet, one inch tall and only a little more than eight feet wide. It is solid, sturdy, and impermeable. Without a “front” or a “back,” the sculpture holds time and space in three dimensions, and then, perhaps there is the suggestion of another dimension, the passage of time. Maybe this is why its placement near the entrance to the UNC Hospitals is so poignant. Unmoved by the reason you must enter or leave the hospital, it offers a moment of reflection. Pause and ask: Am I the next generation? Are you? Will the hospital be the last place I see? Is this the beginning or the end? Am I holding on or being held? We are all somewhere in the middle, taking a pause and in that moment, waiting with anticipation for what will come next.

- Amanda Millay Hughes is the senior director of development and strategy at Duke University Chapel. An artist and writer, Hughes spent many years at the Ackland as a staff member, docent, and participant in The Five Faiths Project. She leads the monthly Drawing in the Galleries program at the Ackland.

- What word first comes to mind when you view the sculpture? Whether the word is about an emotion, the shape of the sculpture, or the material it’s made with, name what you see that gives you that impression.

- Describe the forms that make up the sculpture. How would you characterize them individually? What is the nature of their relationship? What do you see that makes you think that?

- Where do you notice negative space, or the space between and around the object? How does this interact with the positive space of the artwork, or the solid form of the piece? How does this change as you move around the sculpture?

- Consider where the sculpture is installed. What effect does the location have on the sculpture? Consider the artwork’s material and title.

- Visit Allan C. Houser’s website to read about his life, view images of his artwork, and watch a virtual tour of the outdoor sculpture garden with his sculptures.

- Explore select works of art by Indigenous North American artists in the Ackland’s collection in Ackland Upstairs from January 10 through May 12, 2024. Pick up a self-guided tour on the F.A.M. Cart in the Ackland’s lobby that highlights these six artworks.

- Allan C. Houser was a Chiricahua Apache artist. Click here to view the Native Land Digital map, and click here to view and learn more about the Chiricahua Apache territory.

- Watch “The Dean of Stone,” a PBS special about Allan C. Houser that aired in 1992. See the artist at work and listen to him talk about his artistic process and sources of inspiration. This shorter video also includes the voices of Anna Maria Houser and Philip Haozous.

- Read a post on the Ackland’s website about the installation of Next Generation II at the UNC Hospitals complex and the 2011 exhibition of works that connected to the Houser sculpture.

- Click here for Google Maps directions to Next Generation II at the UNC Hospitals complex.