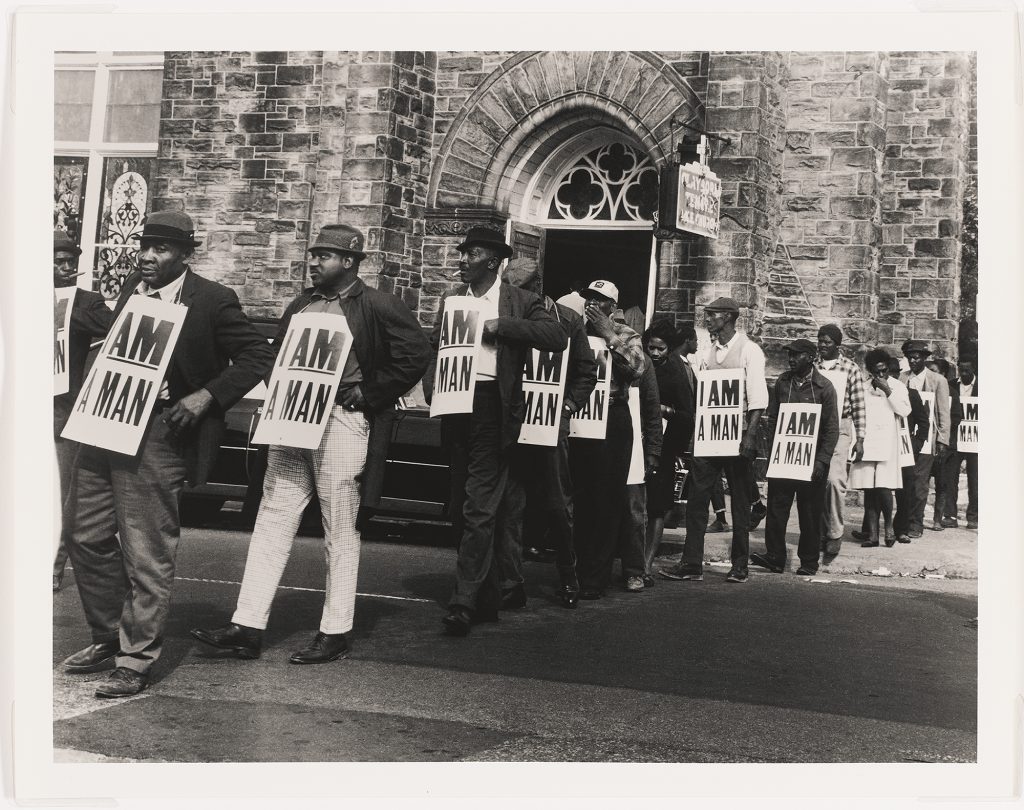

“Sanitation Workers” by Ernest Withers

Click on the arrow below to listen to an audio description of the featured work. Click on the transcript button to read the description.

The black and white photograph is a little larger than a standard sheet of paper with hues ranging from bright whites to soft silvers and opaque blacks. It depicts a line of African American protestors on a city street. While roughly fifteen individuals are visible, the group seems to extend beyond the borders of the image. Most of the figures are Black men wearing variations of fedoras, dress pants, sport coats, and shiny work shoes. Two women in low heels, work dresses, and cardigans appear with them. The crowded composition draws our attention to the large rectangular placards hung on the men’s chests. The large signboards on nearly all the individuals pictured are uniform in size and typeface. They read “I AM A MAN” with the word “AM” in bold and underlined, giving it additional emphasis. All of the signs are identical, indicating they were printed rather than hand painted. A woman in the back right corner of the print also wears a sign, but its multiple lines of writing, which appears to be handwritten, is not legible.

The group of protestors are marching forward together in one proud line. The photograph was taken while the people in this line were in motion, as there are variations in the figures’ gestures and stances. Some people have their hands on their hips, others are wiping their faces, and everyone is walking with a different gait. Everyone whose face can be seen has a serious or furrowed facial expression. A few have their heads down. Many of the men in the front of the line is looking over to the left, perhaps at something happening beyond the frame of the print. No one is looking directly at the camera.

The protesters are crossing a road that has multiple sections of darker and lighter colored asphalt. The asphalt’s uneven coloration and white traffic markings indicating a well-trafficked street. The marchers occupy the entire street preventing overall flow of traffic. A sleek, black car is shown stopped on the side of the road behind the line of people. Just beyond the car is the arched doorway of a brick building, which dominates the background. The archway features petal-like Gothic embellishments, which complement the stain glass windows on the left edge of the photograph. A sign hanging near the entry reads “Clayborn Temple Lake Church.”

When I look at this photo, I see a group of African Americans that want to make a change in their community. The first thing I noticed when I saw this artwork is the complete lack of color. This view is what immediately nudges me as part of the audience toward feeling the same gloominess exhibited by the subjects of the photograph. The use of black and white is comparable in my mind to the segregation that was taking place during the period in which the photograph was taken. Both the lack of color and the signs that read “I AM A MAN” make it so that the tiredness of these subjects is tangible, like if I reach out I may just be able to grasp it.

I see that most of the subjects within the photo are male, but there are also a few women in the line of African Americans. Although I am not able to see the wording on the women’s signs, I wonder if they contained the slogan “I AM A WOMAN” instead of “I AM A MAN?” Would these brave women have tried to fight against both sexism and racism in this protest while knowing what consequences they might suffer? When looking for an answer, I notice that some of the protestors appear to stand tall and fixed on their goal of creating a change, while others are more slouched and jaded in appearance. This leads me as a viewer to believe that it is possible both the men and women knew that this protest could result in harsh consequences, but they were ready to stand strong and fight for what they believed in no matter the cost.

– Riley Peterken is a member of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s class of 2023 and is studying biology with a minor in chemistry

Ernest C. Withers, American, 1922-2007, Sanitation workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for a solidarity march, Memphis, Tennessee, March 28, 1968. I Am A Man was the theme for the Community on the Move for Equality (C.O.M.E.), which helped spearhead the Sanitation Workers’ strike., 1968, printed 2001, gelatin silver print on fiber paper, 10 15/16 × 13 15/16 in. (27.8 × 35.4 cm), Ackland Art Museum, Ackland Fund, 2017.26.10.© Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. courtesy of the WITHERS FAMILY TRUST.

I see a line of African Americans — respectable, but dejected men and women wearing signs that read I AM A MAN. They all seem to be looking at something ahead of them to their right and away from the photographer, although I am unable to visualize what exactly they are viewing. It’s a sad photograph that depicts the need of these African Americans to assert their existence in a society that works to diminish their being on a daily basis. I ask myself: what difficulties did these men and women have to face in both their personal and professional lives to get by every day?

While trying to answer this question, I noticed that the marchers are walking in front of a Gothic stone building. This very structure

exudes wealth and power, which is a stark contrast to the people in line who were in such dreadful conditions at work that they had to remind others of the fact that they were living, feeling human beings. Knowing that what lay ahead of them was Dr. Martin Luther King’s visit to Memphis to support them, and his assassination a week after this photograph was taken, adds to the grim frustration of the scene.

– Patsy Keever is a retired middle school history teacher who served as a Buncombe County commissioner and a member of the NC House of Representatives. She is a graduate of Duke University.

I have seen this print a few times being passed around, particularly in recent months. It’s certainly a harrowing sight considering that we find ourselves today surrounded by similar acts of protest, in a nation that has been frozen in time since we found ourselves at the top of the post-WWII pile.

I’ve seen copies of those signs in civil rights museums, and one thing that stood out from their monochromatic counterparts is that the lettering is actually a bright crimson in person. Perhaps this was symbolic of the leftist aspirations of a people subjected to centuries of brutality, or perhaps they were red with the blood spilled from

countless martyrs for a cause that never truly came to fruition.

Either way, I think that we have an obligation as a people, and as a species, to continue that struggle which has been carried on for so many years. The struggle for true emancipation. For true equality. We are all of the same flesh, and of the same crimson blood. We are all men.

– Henry Stanley is an activist and student at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts who helped to organize marches in Winston-Salem during the George Floyd protests last summer.

I see men and women walking in succession outside a church with signs that say ‘I AM A MAN.’ I see a church as a place of safety, affirmation, and communion. I see solidarity, frustration, and anger. I see determination. It’s in their faces as they walk. I see folks who want to be treated properly and respected. I see folks who know the struggle they face in a society that sees them as less than. I see their faith and resilience sustaining them as they move regardless of the opposition they know they will see.

This is a powerful reminder of the kinds of struggles that have been fought by Black people in this country. A reminder of what it takes to make change. The courage to stand for what you believe in.

– Christopher Massenburg is the Rothwell Mellon Program Director for Creative Futures at Carolina Performing Arts, an executive director for the arts, musical artist, & instructor at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Ernest Withers got his start as a photographer of the Civil Rights movement during the trial of the murder of Emmett Till. Till was lynched after a white woman falsely claimed that he had inappropriately touched her. How might Withers’s photographs have furthered the Civil Rights movement?

- The 1968 protest shown in this photograph took place after the deaths of two Black garbage collectors due to a truck malfunction. The city of Memphis’s response was inadequate, leading Black workers to protest. In this photo, the demonstrators are carrying signs that read “I AM A MAN.” What does this slogan mean, and why do you think the protesters used it? How does it emphasize the role of gender in these protests?

- Martin Luther King Jr. played an active role with the Sanitation Workers’ Rights Movement. Only a few days after this photograph was taken, King was assassinated. How does this context change your perception of the photograph?

- How does the church in the background behind the marchers influence your interpretation of the meaning of this photograph?

- In Preston Lauterbach’s new book, Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers, he claims that Withers worked as an FBI informant during his career, sharing information about the activists with the federal government. What additional meaning does that information add to the photo? Do you think it affects Withers’s legacy as a Civil Rights champion?

- How can you relate Withers’s photograph to the Black Lives Matter movement? How can we compare this image to modern pictures of crowds of protestors facing riot police in 2020? What has improved from the time and circumstance of this print and what problems still exist today?

- Ernest C. Withers helped to photograph and document the major events of the 1960s, including key moments of the Civil Rights Movement in America. To see more of these photographs, explore the digital archives of the Withers Collection Museum & Gallery online.

- Understand more about Withers’s role as a photojournalist and an FBI informant in an article from The Intercept.

- Watch an interview with Withers about his involvement in documenting the trial of Emmet Till’s murderers.

- Read more about the history of the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

- See a letter written regarding the Community on the Move for Equality, the group of ministers that helped organize the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

- Explore more photographs from the Civil Rights Movement that assist in telling a bigger picture.

About the Art

- Ernest C. Withers took this photograph on March 29, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. The photograph depicts a line of sanitation workers on strike, specifically in a solidarity march from Clayborn Temple, the church they are standing next to, to Memphis City Hall.

- The march was originally scheduled for March 22 but was postponed because of a snowstorm. Civil Rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. was present at the Sanitation Workers’ Strike and gave his speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” at the event. A week after leading the march, he was assassinated.

- The sanitation workers all hold signs that Withers had helped make the night before. Each sign reads, “I AM A MAN.” This slogan was associated with the group Community On the Move for Equality (COME), which led the Sanitation Workers’ Strike in Memphis. The workers wanted to emphasize their humanity in the face of dehumanizing working conditions and racial prejudice.

- The 1968 Sanitation Workers’ Strike took place in response to dangerous working conditions, poor safety measures, and low wages for sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. Most of the city’s sanitation workers were Black and were paid less than their White counterparts. Furthermore, pressure for the strike increased when Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two Black sanitation workers, were crushed to death in a garbage compactor while taking shelter from the rain. The strike took place eleven days after their deaths, and both Cole and Walker were honored in a march during the strike.

- The march was envisioned to be a peaceful event, led by Dr. King. However, after just six blocks, it fell apart. Leaders, including Dr. King, were forced to leave because of chaos, violence, and interference. Policemen got involved, and the marchers faced tear gas, clubs, and looting of downtown businesses. The march ended in disaster, both for the workers and for COME’s desire to bring attention to their plight through nonviolent action. The march was rescheduled for December of 1968, with the hope that Dr. King would again lead them. Unfortunately, that would never happen.

About the Artist

1922: Ernest C. Withers born in Memphis, Tennessee.

1936: Around his freshman year in high school, Withers begins experimenting with photography.

1942: Withers marries his high school sweetheart, Dorothy Curry.

1943: Withers joins the Army and his first child is born. In the Army, he requests photography training and begins to study at the Army School of Photography in Camp Sutton, North Carolina.

1945: Withers begins work as a commercial photographer while stationed on the island of Saipan.

1948: Withers becomes one of the first Black police officers in Memphis.

1955: Withers gains national recognition after photographing the trial of Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, the murderers of Emmett Till.

1955-56: Withers photographs the Montgomery bus boycott.

1957-58: Withers photographs the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

1968: Withers covers the Sanitation Workers’ Strike in Memphis, Tennessee.

1998: Withers is inducted into the Black Press Hall of Fame.

2007: Withers dies in his hometown of Memphis, Tennessee.

2010: Withers is revealed as having been an FBI informant between 1968-1970.

Created by:

Sandra Becerra Sandoval, Armistead Brundage, Carson Elm-Picard, Valeria Galvez Bautista, Samar Hassan, Lauren Heflin, Nick Hylton, Alayna Kropfelder, Zizhou Lu, Aida Mitchell, Mackenzie Parker, Riley Peterken, Madi Radford, Chelsea Ramsey, Emily Roper, Margaret Stathelson, Mackie Tygart, Melissa Yu

Edited by:

Michelle Fikrig and Maggie Cao