The idea for this blog post and title are indebted to artist and conservator Stacey L. Kirby. My conversation with her reframed how I think about conservation, especially of African art objects. Her sculpture Bronzed VALIDity is in the Ackland’s collection.

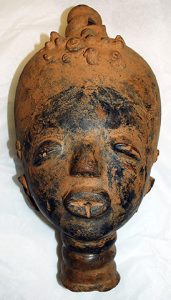

The two terracotta portrait-heads produced by unidentified Akan artists on loan from Rhonda Morgan Wilkerson ’86 (PhD) are likely disembodied. Although objects of this type in museum collections most often appear as these two do, consisting of only the head, they would have originally been part of a larger vessel or figurative sculpture. The aesthetic preferences of the art market in the West, as well as the original collectors’ own assumptions about what art is, influenced what was deemed worthy of keeping. These are decisions that ultimately continue to shape the experience of visitors to the Ackland today.

Once an object enters the collection of a museum, the institution needs to make choices regarding its care. Inevitably, practices of preservation and conservation raise questions: What is the art object? Is it the way that the object would have appeared to its maker at its moment of “completion”? Or does the art object extend to the material accumulations of an object’s history? What is worth conserving? As I hope to show, the answer depends, at least in part, on the cultural origin of the object.

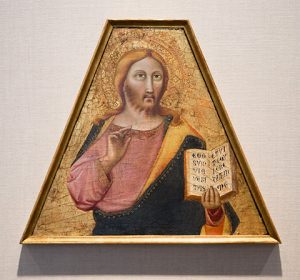

Like the terracotta portrait-heads, Francesco Traini’s Christ Blessing (currently on view) was once part of a larger work, in this case an altarpiece. Years of use in smoke- and incense-filled churches had a darkening effect on the work’s surface. This can be seen in a photograph of the condition of the work before cleaning and restoration was undertaken following acquisition in 1961 (not shown here). The stated goal of this project was to restore the work to as close to its “original” state as possible.

In contrast, the terracotta portrait-heads, and the diviner’s necklace created by an unidentified Yorùbá artist that was on display in the same installation as the heads, continue to bear the material accumulations of their respective histories. Likely placed on the ground as part of funerary ceremonies, the two terracotta portrait-heads have noticeable encrustations of sediment. The biography of the necklace is evoked by the torn strands of beads, discolored beadwork, and the presence of dirt, all products of the changes of the constitutive materials over time, interactions with sunlight and dust, and use by Ifá diviners.

Not every work of African origin in the Ackland indicates use or age. I utilize this cross-cultural comparison not to suggest an absolute rule but rather to highlight the expectations that shape the ways viewers, curators, and conservators respond to objects produced in different cultural contexts. The presence of dirt — itself an ideologically-loaded term — speaks to a history of Western desire for proving the authenticity of African art works based on evidence of use. There is an unavoidable overlap as well with stereotypical colonialist conceptions of the African continent and its peoples as more primitive or closer to nature. In contrast, Francesco Traini is retroactively elevated to the status of genius artist whose creative vision must be restored.

Decisions regarding what portions of art objects are worth conserving are inevitably influenced by the expectations placed on the works themselves. These considerations differ based on culture of origin. In responding to these expectations, we can understand conservation not as a neutral act but rather as an interpretive or even creative one that can affect a visitor’s experience at an art museum to perhaps even a greater degree than the artists of the works on display.

In my next post, I will use a work of art by a contemporary artist as a lens through which to further explore this conclusion — that conservation is more properly considered as a creative act — and to illuminate some of the other factors at play in shaping the experience of viewers of a work of art in a museum context.

Michael Baird was the 2022 Joan and Robert Huntley Scholar and is a PhD student in art history at UNC Chapel Hill. He curated the exhibition Beyond Wood: Works from the Collection of Rhonda Morgan Wilkerson ’86 (PhD) at the Ackland. His research focuses on art education in Uganda from the colonial period to the present.

Image credits:

Unidentified artist, Akan culture, Portrait Head (probably from Funerary Vessel or Figure), 20th century, terracotta, 12 × 5 3/4 × 5 1/2 in. (30.5 × 14.6 × 14 cm). Lent by Rhonda Morgan Wilkerson PhD, L2022.17.1.

Unidentified artist, Akan culture, Portrait Head (probably from Funerary Vessel or Figure), 20th century, terracotta, 9 × 7 1/4 × 5 in. (22.9 × 18.4 × 12.7 cm). Lent by Rhonda Morgan Wilkerson PhD, L2022.17.2.

Francesco Traini, Italian, Pisa, active 1321-1345, Christ Blessing, c. 1335, tempera and gold on wood panel, the William A. Whitaker Foundation Art Fund. Conservation treatment for this painting, completed in 1991, was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. 61.12.1

This is very thoughtful and interesting Michael. I’m looking forward to the next installment. I’d also love to hear you talk about this subject at a conservation conference, and I think many other conservators would be interested too. Conservation is always evolving, just like the rest of the museum world.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Grace, and for all of your help in shaping this project!