An Explanation

There are few seasons as vibrant as spring in Chapel Hill. For some, it’s best imagined as the explosion of azaleas in bloom around the Old Well. For others, it’s the throngs along Franklin Street after a basketball victory at tournament time. For me, it’s the Art Lab’s truck delivering the most contemporary of contemporary art to the museum. As many of our faithful visitors are aware, the Ackland annually presents a curated exhibition of selected works by the graduating class of UNC-Chapel Hill students receiving their Master of Fine Arts degree in studio art. Experiencing their art and celebrating their achievements is a tradition at the Ackland that comes with every April.

And so it would have been this year on Friday, April 24. But then March happened.

Let me just say that when guest curator Saba Taj suggested this year’s title – In Vulnerability – way back in January, no one anticipated just how much it would be capturing the zeitgeist three months later.

As much as we love welcoming both our participating artists and our visitors from campus and community, COVID-19-related circumstances prevent us from opening our doors to showcase the immense talent that lies just next to us in Hanes Art Center. It is apparent that people throughout the world are struggling to adapt to a new normal, and we museum professionals are fervent believers that art is a powerful force in aiding self-care. While it certainly is not the same as an actual visit to our galleries, it seemed only right that we should, at the very least, give visitors a glimpse at what everyone had worked together to create in this exhibition.

If you’re wondering why we don’t just present the exhibition virtually, it is because the works selected are often not available in their final forms until an Ackland installation opens, and we felt it was important to fairly represent all of the graduates. While artists working in more traditional media like painting or photography can sometimes formally photograph their works in advance, other artists who present constructed environments often cannot fully realize such site-specific works until they’re physically installing them in our gallery spaces. In the coming weeks, I will provide a blow-by-blow on our blog of how we go about organizing this annual endeavor so that visitors understand just how much preparation it requires.

Instead, we have assembled materials to give a flavor of In Vulnerability: Selected Works by the MFA Class of 2020. There is a video walk-through of the proposed gallery layouts created by Nathan Marzen, our head of exhibition design and installation, using the same modeling software that he employs to imagine every exhibition at the Museum. In the second half of this blog post, Saba Taj has written about the themes that were present in her conception of the show, with an eye to describing how much more pertinent they become with each passing day. And we have a carousel of images of one or two representative works by each of the artists.

Of course, the true luminaries of this project are the participating artists: Cassidy Kulhanek, Sally Ann McKinsey, Chloé Rager, Natalie Strait, and Emily Hobgood Thomas. As I write this, they are busy defending their thesis projects, completing exams, and submitting grades for their own students. Nonetheless, in the coming weeks, we will be uploading recorded zoom interviews with some of them to give visitors a chance to hear their voices directly. Please check back on our website and follow our social media accounts for news of those additional materials.

And please join the Ackland in extending its hearty congratulations to these students! While this year we were unable to physically present their art, it was an honor to be introduced to it.

Lauren Turner is the assistant curator for the collection at the Ackland Art Museum.

Thoughts from the Curator

In Vulnerability explores the interdependence of bodies and their environments, illustrating that ‘the body is less an entity than a relation, and it cannot be fully dissociated from the infrastructural and environmental conditions of its living.’ (Butler, Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance). These relationships are articulated through works by the five UNC-Chapel Hill Class of 2020 Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art candidates, who interrogate the ways humanity shapes and is shaped by a variety of forces.

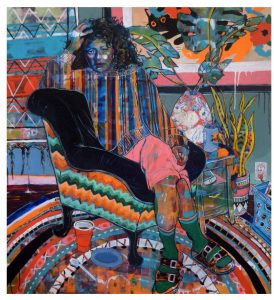

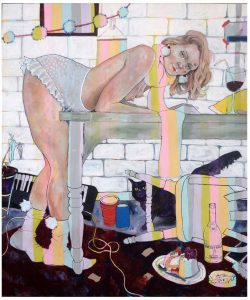

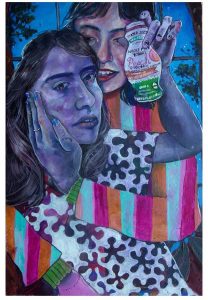

Cassidy Kulhanek employs humor and urgency to call attention to climate change, an acknowledgment of the vulnerability of our planet, and our own survival on it. Emily Hobgood Thomas documents the changing landscape of a North Carolina beach town, emphasizing the dysfunctional nature of development, destructive behind a turquoise facade. The precarity of the state, and our relationship as citizens to the state, is illustrated through sculptural works by Chloé Rager. In portraits by Natalie Strait, painted figures are depicted in moments both tender and mundane, and complicate normative dynamics of the gaze on women’s bodies. Issues of mortality are raised as Sally Ann McKinsey considers rituals of care for the sick and dying in an immersive installation that recalls a hospital room.

This exhibition presents vulnerability — too often perceived of as weakness — instead as an essential quality of agency, and of being alive.

– Proposed introductory gallery text

“However we choose to think of the social body, we are each other’s environment. Immunity is a shared space.” – Eula Biss, On Immunity: An Inoculation

In Vulnerability feels uniquely relevant in these times of global pandemic. Individually and collectively, we are faced with the vulnerability of our physical bodies. With each point of transmission, the virus’s spread highlights that the relationships between us are vast and penetrating. Our lives are not made separate by the borders of our skin or our nations, or even the taxonomy of our species.

Natalie Strait’s paintings now feel oddly reminiscent of quarantine. Often set in interior or home spaces, Strait plays with the boundaries between the figures and their settings, and the depictions exist at the edge of public and private. We encounter women in various states of dress and undress—an aspect that feels more casual than sexual (as in, “what’s comfortable to wear while eating snacks on the couch,” or, “I’m still a little drunk from last night”). In some, we witness tender moments of touch. In others, there is something distinctly Instagram-ready about the way the figure looks back at us – or doesn’t.

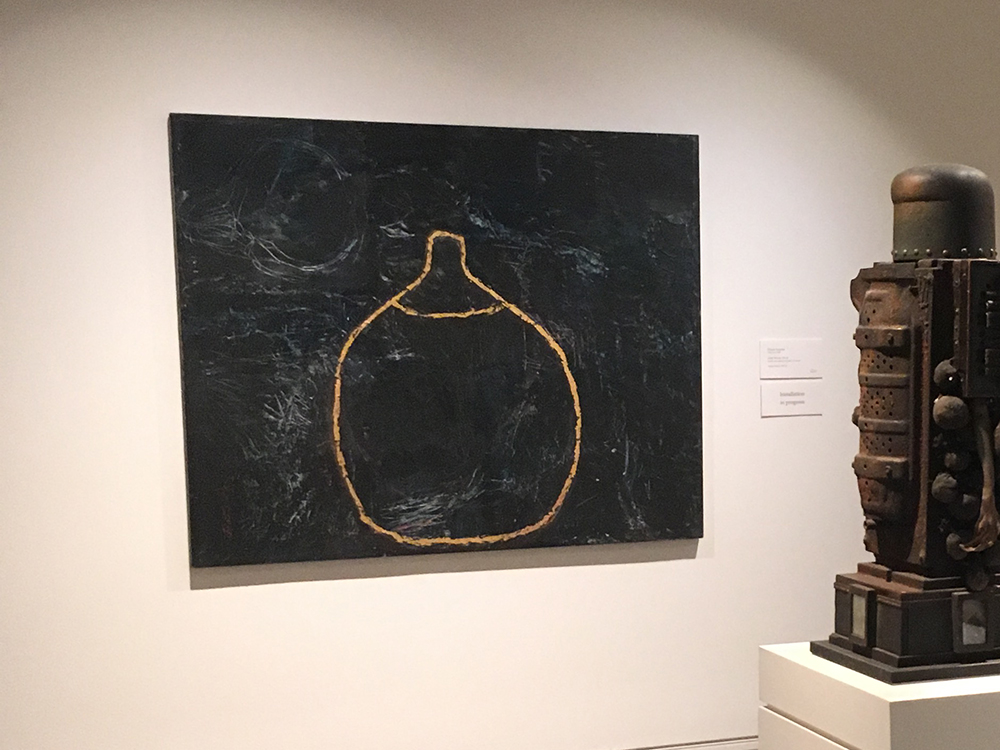

Chloé Rager creates poetic sculptures that speak to the relationship of the state to its constituents. The state is represented by materials of infrastructure like concrete and metal—heavy, masculine, and seemingly impenetrable. In Sweet and Low, Blonde Winch, and Interstructural Breathing, Rager penetrates these materials with sugar, with a handful of her hair, with the sound of her breathing. As though presenting artifacts or heirlooms, she records the degradation of sidewalks and roads with a collection of rubble kissed by neon marking paint in Chromaruin, and casts of potholes in Pothole Archive, glowing in shades of pink.

A small beach town that Emily Hobgood Thomas calls home, Morehead City has an economy that relies heavily on tourism. In Transient Places, she documents abandoned buildings in Morehead City in digital photographs, decaying sites where local businesses once thrived. There is something archaeological about the images, as though we are looking into the past and peering into spaces that are out of sight and empty, but full of ghosts. In Thomas’s collage pieces, physical and digital images are cut, grafted, and manipulated. Undulating and layered, we understand that the city is in an uneasy process of development and deterioration.

Also concerned with the destructive side of development is Cassidy Kulhanek. Utilizing interdisciplinary approaches including text, installation, and performance, she presents works that warn of the impending climate apocalypse. Her approach is at times incredibly sincere and urgent, and at others, morbidly satirical. Plastic Planet Properties, a dystopian real estate company, offers beachfront properties in the Piedmont region, speaking to both the rising sea levels and the terrible potential of disaster capitalism. Such imaginings of the not-so-distant future are punctuated by a black and white banner that shouts to us, “We Have Never Been Closer to the End.”

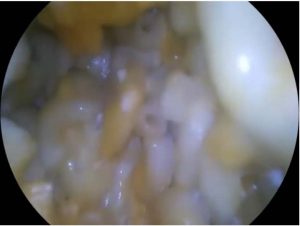

Sally Ann McKinsey’s installation Code Blue is especially poignant as we navigate how to demonstrate care in a time of crisis and social isolation. In this surreal hospital room, McKinsey extracts and recombines rituals and materials of care found in hospital settings and community settings. Textiles from hospitals that signal sterility and objectivity are used to weave rugs and blankets, a casserole is explored through endoscopy, and a bed is suspended from IV tubes, collapsing gently into itself like a body at rest. Her work asks, “What are the cultural systems in place to keep the dying alive, to manage chaos, or to control mortality?”

The coronavirus, although microscopic, might show us just how sick we really are. I think we can understand a society’s ability to survive by how it cares (or doesn’t) for its most vulnerable. Right now, we center the elderly and immunocompromised, but much more must be done for the essential workers who regularly risk exposure (especially those who are unable to afford getting sick and unable to afford staying home), for those who are being held in close quarters in detention centers and prisons, for those without homes to stay home in. Vulnerability is frightening because it suggests that we do not have individual power over our lives and can be harmed. But it also reveals that we are inextricably connected, and that is how we survive. I find some comfort, and resolve, in that.

Guest curator Saba Taj is a visual artist based in Durham, North Carolina, and a 2016 graduate from the MFA program at UNC-Chapel Hill. Currently, Taj is the 2019-20 Post-MFA Fellow in the Documentary Arts, as part of the Documentary Diversity Project at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies. She is the former Director of The Carrack Modern Art.

Art image credits, top to bottom, left to right:

Chloé Rager, American, born 1994, Blonde Winch (detail), 2019, concrete, brass-plated chain, and hair, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist.

Natalie Strait, American, born 1997, from the collection of the artist:

lonely weekend, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 52 x 48 in. (132.1 x 121.9 cm).

rosé all day, 2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, 60 x 45 in. (152.4 x 114.3 cm).

daylight savings is a bitch, 2019, oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in. (91.4 x 61.0 cm).

Chloé Rager, American, born 1994, Blonde Winch, 2019, concrete, brass-plated chain, and hair, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist.

Emily Hobgood Thomas, American, born 1995, from the collection of the artist:

320 NC Highway 58 II, from the Transient Places series, 2020, photograph.

3300 Arendell St III, from the Transient Places series, 2020, collage.

Cassidy Kulhanek, American, born 1993, Plastic Planet Properties, 2020, website. Collection of the artist.

Sally Ann McKinsey, American, born 1988, Family Recipes: Macaroni, from planned Code Blue installation, 2020, video, 4 minute, 32 seconds. Collection of the artist.