Janet Dubinsky, PhD, is a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota who was involved in organizing the exhibition The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. As a researcher, she is interested in mitochondrial permeability. She also has a program, BrainU, which engages teachers in teaching about and applying neuroscience in the classroom. Dr. Dubinsky is a graduate of UNC-Chapel Hill. She talked with Director of Communications Ariel Fielding on a recent visit to the Ackland to see The Beautiful Brain.

How did you come to study neuroscience, and why did you choose UNC?

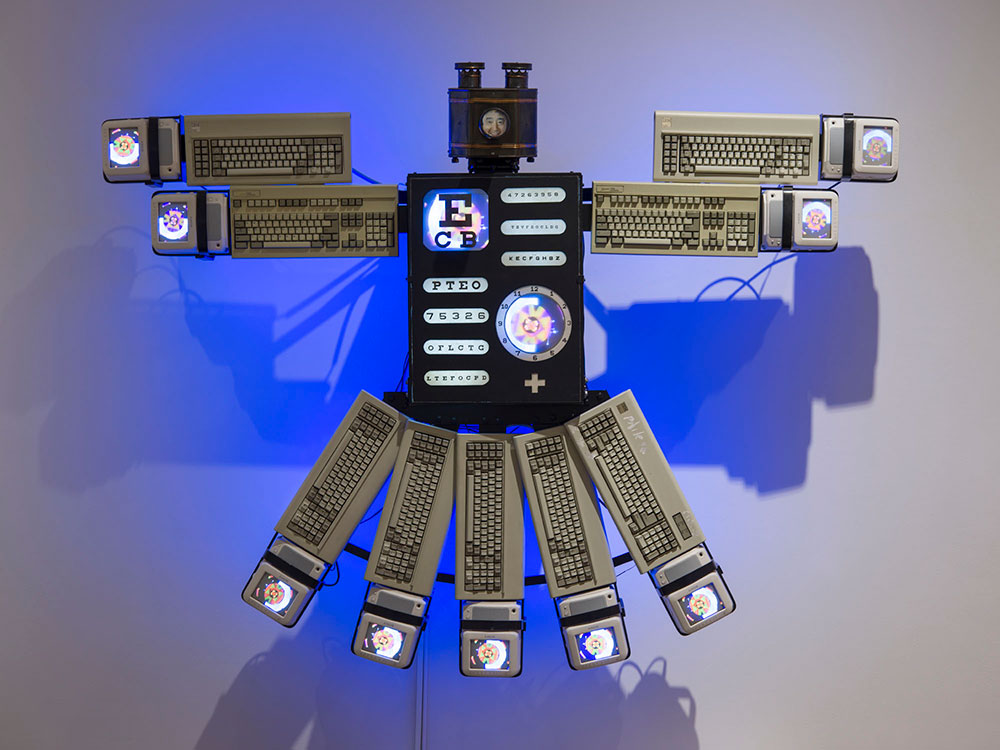

Well, the brain is in charge of everything we do. At the time I went to graduate school, we were just beginning to really comprehend in a concrete way some of the discrete building blocks at the molecular and cellular level that contribute to brain function, and it was very exciting. I wanted to be a part of that. I had worked for many years doing computer programming for small laboratory computers when they were first built; they were made to take biological signals from real experiments and digitize them. Most of the labs that I worked in were neuroscience labs, so having been a part of that process from a technician’s point of view, getting my PhD was the next step — to see if I could myself enter the field and make a contribution.

One of my undergraduate advisors suggested I look at UNC, and I did. Ed Perl [Edward R. Perl, Chair of the Department of Physiology from 1971-1987] called me and said, “Please come,” so I did. He was a very good persuader.

We have some of his slides in the show — Cajal’s slides that were in Edward Perl’s collection.

That’s the most exciting piece for me. We didn’t have them at any of the other sites. Those are really very precious.

It’s extraordinary that they were already here in Chapel Hill.

I didn’t remember them when we put the exhibit together. I might not even have known about them, though maybe there was something in my training — those fragments of conversation when you’re young don’t always come back when you’re older. The Cajal Institute for many years would give things away to visiting scientists. All of these drawings had been stored in drawers in a closet for decades, and the material is precious historically and from the point of view of the field. But they didn’t have money for honoraria, so that’s what the Cajal Institute would use — Cajal’s slides or other materials. It became its own currency.

Tell me about your involvement in The Beautiful Brain. How did the exhibition get started?

The exhibition got started because Alfonso Araque, who had worked at the Cajal Institute, joined our faculty in Minnesota. He knew where the Cajal drawings were, he knew they were not displayed, he knew how precious they were to the field, and he knew how artistic they were, because he’d seen them himself in person regularly. He went to another colleague, Eric Newman, who came for the opening [of The Beautiful Brain at the Ackland]; Eric has connections to the art world in Minneapolis-St. Paul. His father was a nationally noted portrait photographer. Alfonso and Eric went to Lyndel King, who is the director of the Weisman Art Museum, and showed her some of the published drawings in various books. Immediately she wanted to do the exhibit. They decided they were going to put the exhibit in a historical context. So they went to the History of Medicine Library to have the librarians pull appropriate anatomical drawings of the brain prior to Cajal.

Then they decided that they also wanted to show contemporary neuroscience, and they came to me, because I do a lot of public communication of neuroscience. I was asked to do the contemporary side. At the same time, we all began to work on everything together. We formed a really close team, and that part was just as exciting as anything else: working together with Lyndel and her staff at the Weisman to communicate the neuroscience and the art of Cajal. The exhibit had this dual purpose that has blended so perfectly at all of the different sites. It’s been really exciting to see how the exhibit has been received.

Did you imagine that it would be so successful? When the Ackland is open, there are always people in the exhibition, our tours are very popular, and our public programs, many of which have been organized in collaboration with the UNC Neuroscience Center, are always full.

We had no idea how it would play in the art world. Brains usually draw attention because everybody has one, and everybody wants to know how it works inside themselves. So there’s always something personal about a brain exhibition. One or two of Cajal’s drawings had been displayed publicly in different galleries, one at the Tate, and one or two at a gallery in Istanbul, and then there’s a set of six on display at the NIH (National Institutes of Health), but you can’t get to those because the NIH campus is closed, so that’s not really a public display site. We knew there was an audience, but we had no idea how large. His works had never been displayed in a museum setting, or even as a body of work together. Scientifically, all of his works are published, and you have some volumes of the published work on display, but an art museum is a whole new venue for him. Considering his original desire to become an artist as a young man, I think it brings Cajal full circle. It’s very, very exciting. The galleries have been full everywhere. Part of the learning process for me in helping put together the exhibit was to see how all the different sites reinterpret it. I’ve been to all the locations. It’s just so exciting!