When I first began my research as the 2023 Huntley Fellow at the Ackland Art Museum, I intended to study both the Ackland’s Model Altar (an altarpiece with doors that open and close) by the Altötting Master (German, active first quarter of sixteenth century) and the North Carolina Museum of Art’s figure of a female saint by Tilman Riemenschneider (German, 1460-1531) within the context of the rise of unpainted German wood sculpture in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. To the naked eye, both sculptures appear completely, perfectly bare. And Riemenschneider is indeed famous for his large oeuvre of unpainted wooden sculpture, a phenomenon largely unheard of in Europe prior to the fifteenth century. I, like others, assumed both sculptures were part of the same move to embrace the natural appearance of wood and leave sculpture unpainted.

Archival research into the Altötting Master altarpiece led me to a photograph from the 1940s that appeared to be the same object; the dimensions matched, the compositions matched perfectly, and there was even a description attached to the 1940s photograph that noted the existence of indecipherable writing on the back of the object, which matches the Ackland’s. However, this photo, although in black and white, clearly showed a sculpture that was painted and gilded, and that is not remotely how the sculpture appears today. Seeking to confirm that it is indeed the same sculpture, the Altötting Master Model Altar was removed from display so that conservator Mark Erdmann and I could study the surface of the sculpture with varying lighting conditions and magnification levels in a hunt to find evidence of lost paint and gold.

Using ultraviolet light to examine the Ackland’s altarpiece in a darkened room, we were shocked to find a vast spider web of areas that fluoresced under the blacklight. This indicates that those glowing areas were the result of a conservator’s intervention long after the sculpture was made in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. Although it appears to be the same as the wood itself to the naked eye, many lines of a brown-dyed waxy infill were used to smooth the surface of the sculpture and replace losses due to what was perhaps the use of a caustic solvent to remove paint. These lines roughly followed the grain of the wood, and thus quite a lot of the soft wood between layers of the hard wood were lost. And only deep in a few crevices of the sculpture did we find the littlest specks of remaining pigment and gold, which indicates that yes, this sculpture was once painted and gilded, and at some point in its history, its surface was remarkably aggressively stripped and subsequently convincingly homogenized.

In the photograph on the left, the sculpture is shown in the 1940s, when it was still painted. In the center photograph, Mark Erdmann, conservator at Erdmann Art Conservation, looks at the surface of the Altötting Master triptych with a microscope, explaining to me the significance of his findings during a meeting on July 17, 2023. Though difficult to photograph, this sculpture practically lit up when studied under blacklight, as seen in the photograph on the right, which indicates chemical alterations performed on the surface of the sculpture after its creation in the early sixteenth century.

Thirty minutes away from the Ackland, the NCMA houses a lovely sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider, and it, too, was once fully painted but later aggressively stripped. When the NCMA acquired the sculpture in the 1960s, it was believed to be an unpainted image of Saint Catherine. But in the 1990s, it underwent conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and it was there confirmed that the characteristic sword of Saint Catherine that the sculpture then held was an early 20th-century addition. There was also significant evidence that the sculpture was fully painted but brutally stripped of its paint with an acid like lye and further scraped bare with a blade. Some of the scrape marks remain visible.

The photograph on the left shows the Riemenschneider Female Saint as it appeared when it entered the North Carolina Museum of Art’s collection in the late 1960s. The photograph on the right shows the Riemenschneider Female Saint after conservationists restored and stabilized the sculpture and removed the sword that they discovered was not original. What the figure original held in her hand is a mystery. Close study of the surface of the sculpture revealed traces of pigment and gilding. Tilman Riemenschneider, Female Saint, c.1490-1495, Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest) 68.33.1.

Perhaps similarly caustic methods were used to “clean” the surface of the Altötting Master model altar by a likeminded conservator sometime between the 1940s and the 2000s when the Ackland acquired it. If it were scrubbed with lye, this would explain why so much of the wood grain was dissolved and thus needed filling.

Please see my follow-up posts for more information about why these sculptures might have been stripped of their polychrome surfaces and how the Ackland’s altarpiece made its way from Germany to North Carolina.

Image credits:

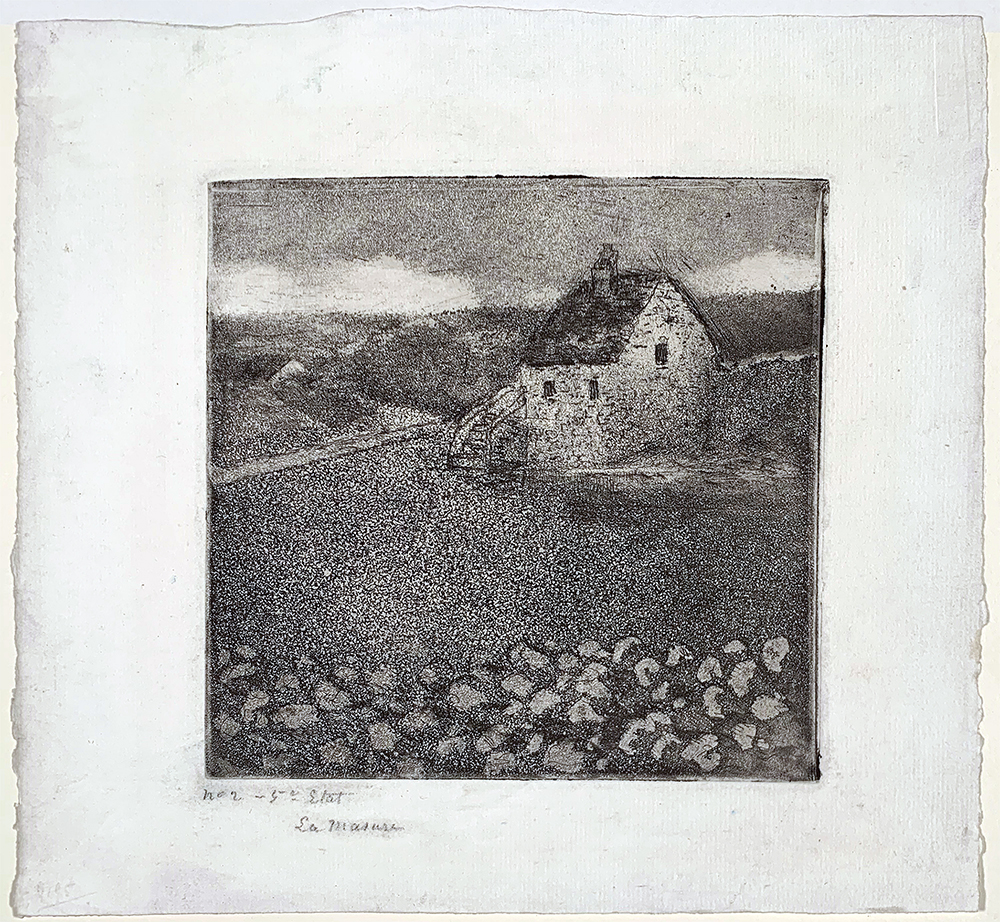

Featured image: Master of the Altötting Doors, German, early 16th century, Model Altar, 1520-1530, linden wood, inscriptions in ink, 35 7/16 x 24 3/8 in. (90 x 61.9 cm). Gift of the Tyche Foundation in honor of the 50th Anniversary of the Ackland Art Museum, 2008.19.

Model Altar composite: Left: https://www.errproject.org/jeudepaume/card_view.php?CardId=1651. Center and right: Hannah Williams.

Before-and-after composite: Tilman Riemenschneider, Female Saint, circa 1490—1495, Lindenwood with traces of paint, 38 x 12 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (96.5 x 31.8 x 21.0 cm). North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 68.33.1