An object’s provenance — its history of ownership — is important information for art museums to know, but often the details in that history get fuzzy and hard to reconstruct as time moves on. As the 2023 Huntley Fellow, I studied the Ackland Art Museum’s triptych, an artwork on three hinged panels used as a focal point for worship, by the Altötting Master (German, active first quarter of 16th century), and I attempted to find more information about this object’s provenance. The Ackland’s altarpiece is winged, meaning that the doors can be open and closed to show various views.

Prior to my fellowship, a curator at the Ackland serendipitously came across an image of Nazi loot in a book that appeared to contain an object suspiciously like the Ackland’s triptych, but it was difficult to determine at the time if the object in the photograph and the object in our collection were indeed one and the same. I spent the summer combing through hundreds of archival documents to ultimately conclude that yes, in the 1940s, our triptych had been stolen from its French-Egyptian Jewish art collector’s suburban Paris home and sent to Germany.

Two men stand in a room full of Nazi-looted art objects at Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany, a primary destination for art stolen from French collections. On the left is a triptych that appears identical to the one the Ackland acquired in 2008. This photo appeared in Robert M. Edsel, Rescuing Da Vinci: Hitler and the Nazis Stole Europe’s Great Art. America and Her Allies Recovered It. (Miller Place, New York: Laurel Publications, 2006), 178.

During World War II, Adolf Hitler ordered the looting of millions of valuable cultural artifacts from across Europe to strengthen German art collections and treasuries. Jewish collections, like the Rothschilds’ famous collection in France, were primary targets for the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce), the group in charge of gathering, organizing, documenting, and shipping art treasures to Germany. Moïse Lévy (or Lévi) de Benzion, a French-Egyptian Sephardic Jew, had a noteworthy art collection comprising hundreds of objects in his villa, the Chateau de la Folie in Draveil, a suburb of Paris. He was born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1873 and made his fortune in department stores. His collection was practically encyclopedic, including ancient Egyptian artifacts, medieval polychrome wood sculpture, and Impressionist drawings. The ERR came to his home in 1941 and took 989 objects to Jeu de Paume, the main Paris waystation for Nazi-looted objects before their processing and transport to one of a handful of locations in Germany. Several of Lévy de Benzion’s artworks were deemed so important that they were sent to Hermann Göring himself, one of the highest figures in the Nazi party.

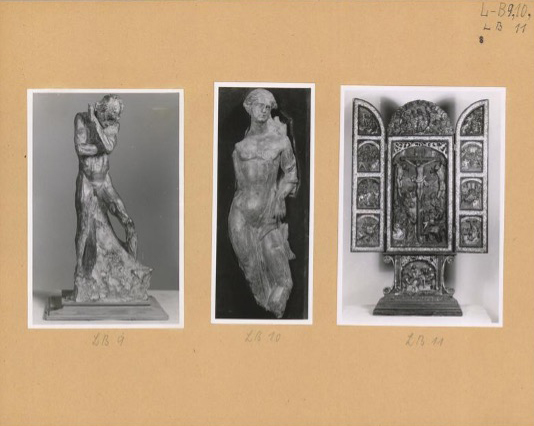

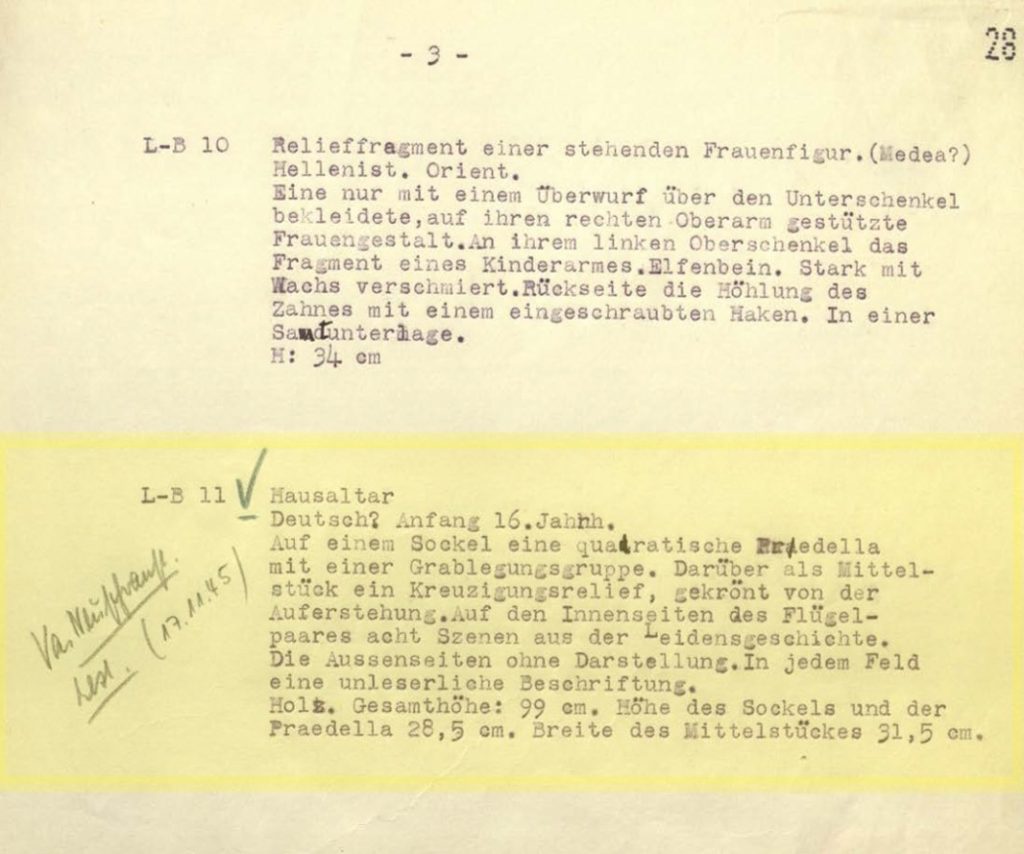

Photos made by the ERR of three of the 989 objects stolen from Lévy de Benzion. The triptych was given the identifier LB 11 (“LB” for Lévy de Benzion). Note the apparent pigment and gilding that is on the triptych, which must have been stripped after it was looted and photographed in 1941 and before it was acquired by Blumka Gallery in New York, which sold the object to the donor who gave it to the Ackland in 2008. See my earlier blog post about the object’s stripping. Bundesarchiv B3232-881-fol.008.

One of the objects in his collection was a limewood triptych — at the time painted and gilt, see my earlier blog post for later changes made to the triptych — illustrating the Crucifixion and other scenes from Christ’s Passion. Documents made during the war show that, with the rest of Lévy de Benzion’s collection, it went to the Jeu de Paume and was later sent in a crate to Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria to await the end of the war. Lévy de Benzion died in Nazi custody in 1943. After the war, in 1945, the triptych was repatriated to France. It was restituted to Lévy de Benzion’s heirs in 1946.

In the highlighted section above, see the ERR-made inventory entry for LB 11, the identifier given to the wooden “hausaltar” (“house altar,” in English) taken from Lévy de Benzion’s home. The text describes the object now found at the Ackland perfectly, down to the presence of indecipherable writing in ink on the otherwise blank exterior of the triptych. Since we were also able to confirm that our triptych was once gilt and painted like the one photographed by the ERR, we can be confident that ours is the same object. In pencil, we are told that the altar went to Neuschwanstein and was restituted in 1945. This is confirmed by another document in French archives. Bundesarchiv B323-276 folio 28.

In March 1947, Lévy de Benzion’s heirs put the collection up for auction in Cairo, Egypt and had a brief catalogue printed. However, the triptych does not appear to have been part of this sale. For the moment, it remains a mystery where the triptych was from 1946 to the early 2000s when it appeared at Blumka Gallery in New York and was purchased by the person who would ultimately donate it to the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill. This globe-trotting artwork officially entered the Ackland’s collection in 2008.

Image credits:

Featured image (left): see above.

Featured image (right): Master of the Altötting Doors, German, early 16th century, Model Altar, 1520-1530, linden wood, inscriptions in ink, 35 7/16 x 24 3/8 in. (90 x 61.9 cm). Gift of the Tyche Foundation in honor of the 50th Anniversary of the Ackland Art Museum, 2008.19.

All other images credited in captions.