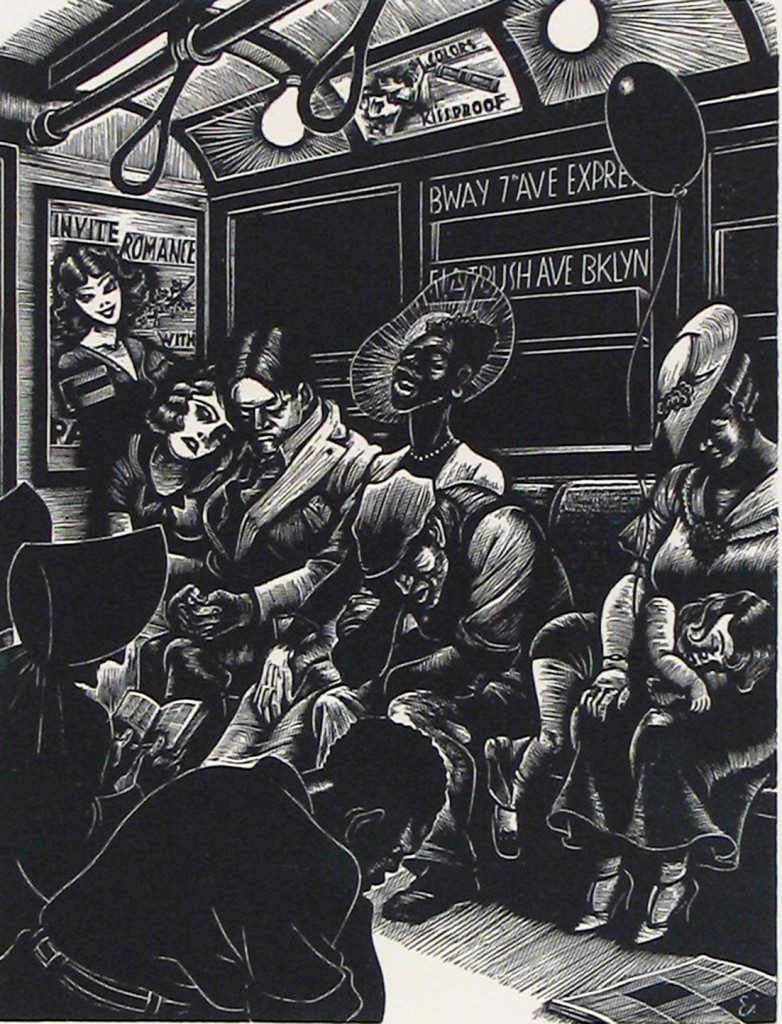

Look at the label next to any painting in the Ackland Art Museum, and the third or fourth line down will give you the title—the name of the painting. Once in a while, with a painting made after 1940, the label will say “Untitled,” a sort of warning that the label will give you no help in figuring out what this painting shows (“Just look hard at it and figure it out for yourself.”).

The strange thing about this is that most paintings made before about 1700 really were untitled. If we see a 17th-century painting labeled Saint Jerome in Penitence, that is not really a title: it’s a description of what the painting shows you (if you know something about Saint Jerome). The first owner of the painting didn’t need to give it a title because he already knew what the subject was; just as you don’t need to write your mother’s name on the back of a photo of her in her wedding dress (although your great-grandchildren may wish you had when they are looking through a stack of old family photos).

Between 1700 and 1900, the way that art was presented to potential owners changed, and publicity became a more important part of art commerce. An artist who submitted a painting to an exhibition—and who hoped that some journalist would mention it in a newspaper—might want to distinguish it from similar paintings by other artists. A distinctive title, like September Morn for a nude bather in a lake, could help. It could also call special attention to one particular aspect of the painting: if you see a landscape titled The Sentry, your thoughts turn to war, and you search for what may be a tiny figure in a broad panorama.

In April 2013, Neil McWilliam, a scholar who specializes in paintings by Émile Bernard, called our attention to an inventory that the painter himself had made in 1901. One entry reads:

La vague – Raguenez – la mer, un tas de varechs, des chênes, une tête de paysanne à l’avant plan

(The Wave – Raguenez – The sea, a mass of “varechs,” oak trees, head of a peasant woman in the foreground)

The artist’s own description identified the Ackland’s Bernard painting pretty clearly, because of the unusual placement of the woman’s head. The trees were there, and the greens and blues of the distance, which Ackland staff had read as hills and valleys, now made more sense as ocean, with a stylized breaking wave. As for “Raguenez,” that is the name of another community on the Breton coast. But what on earth was meant by “varech”? A quick search of the French version of Wikipedia revealed that this is an uncommon French word, describing types of seaweed that are still harvested in Brittany and other coastal regions: for fuel, for fertilizer, and even for animal feed. The seaweed is piled in stacks, covered, and left to dry. Those were also visible in the painting, although they had been previously (mis)identified as haystacks.

The new title, The Wave, and the new information have reshaped my view of the painting. Before, I had seen it as farmland, with some rather strange-looking haystacks and an undefined background. Now it’s clearly a scene on the coast, a beach with a big wave breaking on the shore. Like a digital image downloading, the painting has snapped into focus.

Timothy Riggs, Curator of Collections

Émile Bernard, French, 1868-1941, The Wave, 1892, oil on pulpwood board, mounted on canvas. 22 3/4 x 33 9/16 in. Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ackland Fund. 71.29.1. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Reproduction, including downloading of Émile Bernard works, is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.