About the Ackland

Since 1958, The Ackland Art Museum has been one of North Carolina’s most important cultural resources. We serve broad local, state, and national constituencies as a unit of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The Museum’s permanent collection consists of more than 20,000 works of art, featuring North Carolina’s premier collections of Asian art and works of art on paper — drawings, prints, and photographs — as well as significant collections of European works, twentieth-century and contemporary art, and North Carolina pottery.

The Ackland Art Museum is UNC-Chapel Hill’s local museum with a global outlook. Our location and programs bridge campus and community. We’re free, open, and accessible to all.

We empower you to get close to art – the familiar, the unexpected, the challenging – and connect with the complexity and beauty of the wider world. We provide experiences that spark insight into ourselves, each other, and the world.

Our mission is the art of understanding.

Our invitation to you is to “look close, think far.”

History

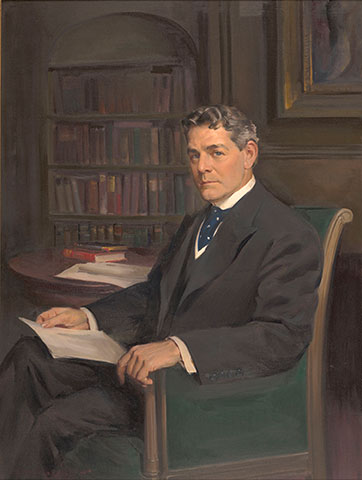

The Ackland Art Museum was founded through the bequest of William Hayes Ackland (1855-1940) to The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Ackland Trust provided the funds to construct the museum building, and that trust continues to provide for the purchase of works of art. Ackland, a native of Nashville, Tennessee, graduated from Nashville University and received a law degree from Vanderbilt University. In 1936, although not a collector himself, he took steps to establish a museum at a southern university. As the words of his tomb suggest, “he wanted the people of his native South to know and love the fine arts.” He was also concerned that the museum be connected with a “great university” with existing cultural interests.

The main source of the family wealth was the fortune built by Isaac Franklin — first husband of Ackland’s mother, Adelicia — who died in 1846. Franklin founded what became the largest slave trading company in the United States, which made him immensely wealthy, and which he sold a decade before his death. Income and capital from the family plantations, and particularly from the forced labor of the people enslaved there, sustained the family’s luxurious and privileged lifestyle after Frankin’s death and Adelicia’s remarriage. This money also provided the inheritance that was the foundation of Mr. Ackland’s personal wealth.

When Mr. Ackland died in 1940, he left his bequest to Duke University. Duke’s trustees, however, objected to stipulations that Mr. Ackland be buried in a museum named after him and that his money be managed by trustees in Washington, D.C. They refused the bequest and started nine years of litigation that resulted in the award of the Ackland Trust to The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, one of the other schools previously considered by Mr. Ackland. Further delays were caused by the unavailability of building materials. Designed in the Georgian style by Eggers and Higgins of New York, the red brick William Hayes Ackland Memorial Art Center was dedicated on September 20, 1958. It comprised exhibition galleries, an art library, classrooms, studios, and offices.

Beginning with a group of objects transferred to the Museum from the University, and with 5,000 prints acquired by UNC-Chapel Hill in 1951 from the estate of New York advertising executive Burton Emmett, a collection was built primarily of European and North American art spanning the centuries from antiquity to the present. Around 1980, the Museum’s acquisitions began to include significant Indian, Chinese, and Japanese objects, and curators devoted substantial attention to drawings and photographs. To help reach visitors with various interests, the Museum’s volunteer docents were reorganized and trained to work with the Ackland’s expanding audiences, including school groups and the town’s retired citizens.

With the creation of the Hanes Art Center in 1983, space formerly occupied by the Art Department was made available for Museum purposes. In 1985, funds were requested for the total renovation of the building. In the fall of 1987, the Ackland closed its doors to the public and renovation was begun. The completely renewed galleries were reopened in December 1990 and March 1992, making available the spaces and enlarged collection at the Ackland today.

William Hayes Ackland and His Money

In the 1940s, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill energetically and successfully fought a legal battle to be named the beneficiary of the Trust established in the will of William Hayes Ackland, who had died in 1940. The will stipulated that the museum be named the William Hayes Ackland Memorial Art Center and that Ackland himself be interred in the building in a marble sarcophagus with a recumbent effigy, as you can see in Gallery 3 when you visit the Ackland.

Mr. Ackland’s fortune stood at about $1.4 million at his death. It had grown eightfold from his original inheritance of about $110,000 (the equivalent of about $180,000 in 1940 dollars), received in 1855, when he was two months old, from his half-sister, Emma Franklin (1844-1855). Emma’s money came from her father, Isaac Franklin (1789-1846), who was the first husband of William Hayes Ackland’s mother, Adelicia (1817-1887), co-owner of the largest slave trading operation in the United States in the nineteenth century, and holder of vast plantations in Texas, Tennessee, and Louisiana, where thousands of enslaved women, men, and children produced a fortune in cotton and timber.

While William Hayes Ackland did not participate in the slave trade or slave ownership — except as a recipient of its labor during his childhood — his inheritance and his subsequent successful stewardship gave him the means to live a life of travel and leisure as he pursued his interests in literature, culture, and art.

The Ackland Trust provided about $900,000 to build the present museum building, and continues to generate annual income, used for acquisitions (representing about 45% of available acquisition funds) and for operations (where it provides about 6% of the annual budget).

Both UNC-Chapel Hill and the Ackland as part of it are institutions originally conceived and funded by families and individuals who profited directly and indirectly from the enslavement of Black people; both places have made a commitment to grappling with structural racism and moving forward in a more just and equitable way. William Hayes Ackland’s story offers one way for the University to engage and teach about its history with race and to reckon with its past.

Accreditation, Policies, & Plans

The Ackland Art Museum is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. As the museum field’s mark of distinction, accreditation offers high profile, peer-based validation of a museum’s operations and impact.

Art image credits:

Unidentified artist, Mughal, Perforated Screen, c. 1605–27, sandstone, 42 1/8 x 40 9/16 x 3 3/4 in. (107 x 103 x 9.5 cm). Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Special Acquisition Fund, 2019.16.3. Photo by Megan Kerns Photography.

Robert O. Skemp, American, 1910–1984, Portrait of William Hayes Ackland (detail), oil on canvas, 48 x 36 in. (121.9 x 91.4 cm). Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. William Hayes Ackland Estate Collection, 58.9.1.